Interview with Cristina Henriquez

Posted by Luke Neima on Tue, 03 Jun 2014

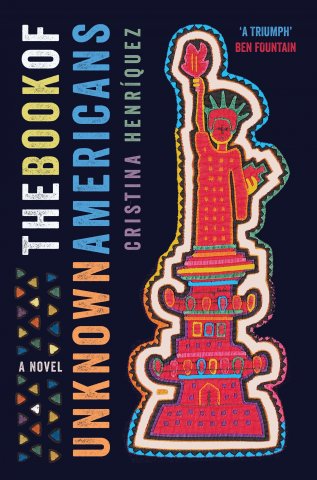

This week we spoke with Cristina Henriquez, a brilliant American novelist who’s been called one of "Fiction's New Luminaries" by the Virginia Quarterly Review. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, Glimmer Train, and Ploughshares, and her second novel (her first in the UK), The Book of Unknown Americans, publishes this Thursday, the 5th of June, with Canongate. It’s a deeply moving tale of one family’s determination to cope with change for the sake of their daughter - a book that gives a voice to a community of people struggling to work and live in a country that isn’t their own.

She took a moment to talk with ABCtales about the subversiveness of literature, the challenge of tackling a second novel, and why we should keep on writing.

How do you feel about the act of writing in the modern day?

The act of writing, literally sitting down in a chair and writing sentence after sentence, almost feels a little bit subversive these days. It feels antithetical to the current moment, which is all about expediency and impermanence, a world of flashing images and tweets and status updates. It requires a kind of sustained attention that seems harder and harder to muster, for me as much as for anyone. When I want to get real work done, now I resort to using Internet disabling software just to keep myself focused, to stop myself from checking my email after every paragraph I complete. Kind of scary, but that’s where I am.

And the state of literature - in a moment when everyone seems to be casting doubtful looks towards Amazon and the changing landscape of publishing, what do you think about where writing - and reading - is going?

I’ve heard it said that writing and reading are basically a subculture at this point. That might be true, but if it is, it’s still a very vibrant subculture, filled with people who are genuinely passionate about books. It’s depressing to see independent bookstores close, of course, and maybe I’m naïve in the face of so much evidence to the contrary to say this, but I do think that the state of both reading and writing is strong, that there are plenty of writers – many, many of them – doing interesting and important work and that there will always be readers, no matter how the words get to them, hungry for that.

What was it like working on your second novel – were you applying a process that you had learned and developed over the course of working on her first book, or did this work challenge you in new ways?

In my limited experience so far, you have to relearn how to write each book as you’re doing it. I wish, after writing my first novel, that it had given me some insight about how to approach a second one, but the most it gave me was a certain degree of confidence – and even that might not be the right word – that if I could do it once, I could do it again. That is, that at the very least I could complete something novelistic in scope from beginning to end.

When I write short stories I purposely try to know as little as possible before I start. I write one sentence and let it lead me to the next, and from that one to the next, and so on. For a novel, that’s more or less my strategy for the first fifty pages, but after that, I step back to assess what I have. At that point, I do outline a bit, although my outlines are nothing formal. They’re more like a list of scene summaries. Alma goes to an English class. Maribel starts school. Etc. So much of writing a novel is about finding the right structure to support it. Novels are such bulky, messy things. You have to have that foundation in place or else the whole thing will crumble. For me, realizing that the neighbors’ stories could exist as interstitial chapters, these punctuations in the larger narrative, was what gave the book shape. They were like lily pads as I was writing; I felt that if I could make it from one to the next, I could keep moving forward through the story.

Your new novel emphasises voices that tend to go unheard – the immigrant community in an ‘impossible America’ - what kind of work went into getting those voices right?

I don’t know that I did get them right! But I tried. I researched colloquialisms and customs from each country represented and tried to incorporate some of that into the testimonials. But I’ve learned that too much research can hamper my imagination, so after a certain point, I relied more on invention, trying to consider what these people might sound like, the nuances in their personal expression.

Identity is also a big theme - how do you tackle such a difficult subject?

Identity wasn’t always an issue for me in my life. It’s become more so as I’ve gotten older and as I’ve written books that have addressed it in different ways. I’ve thought about it more and I’ve been asked about it more, which has led to an even deeper consideration. So I’m at a point now where I have a certain self-awareness about identity and about how my identity is perceived by others. I think that translated a bit to my characters in this novel in the sense that may of them are aware of how others see them. Micho Alvarez, a photographer from Mexico, tackles it most forthrightly during the course of his narrative, listing off a number of negative and misinformed stereotypes that people have about Mexicans. Mayor, a sixteen-year-old Panamanian boy, talks about how the kids at school tease him partly on the basis of his ethnicity and how, at the same time, he feels sometimes that he’s disappointed his own father by not being Panamanian enough. It’s a recurring theme in the book and one that for me personally was fruitful to explore.

Finally – why should we keep writing?

Why write? There are so many ways to communicate these days – we can tweet our thoughts, post on Facebook, send an email or a text message, record a song, make a YouTube video, a movie on our phones. And yet, maybe all of that is why we need writing more than ever. A piece of writing is a bit of quiet in a noisy world, it’s something we have to slow down to experience and to appreciate, it asserts a kind of permanence – or at least gestures toward it – at a time when everything else seems to flash before our eyes only to be replaced by the next new thing.

Stories help us make sense of our messy world. They pull the threads together and give experience shape. They’re an organizing principle, something that helps us understand what we do, the ways in which we connect, the ways in which we don’t. For all the talk of living in the moment, it’s hard for us to do that. We long to know what’s next, and what’s going to happen after that. We need to believe that there’s a future ahead of every next moment; maybe it’s a way to resist mortality, the knowledge that at some point, for all of us, there won’t be a future moment. Or maybe it’s simpler than that: We’re curious. Curious about what’s around the bend.

Stories also give us a way to connect to each other. In the best of them, we’re allowed entry into another person’s thoughts and feelings. Even if we don’t particularly like a character, we come to know them, to understand them because made the choice to listen to them and to consider them in ways that sometimes it’s difficult to find time to do even with our real friends in our real lives. Reading a story requires a certain sustained attention and the reward, after we’ve given it, is coming out on the other side with an enlarged sense of empathy not only for the character on the page but for the person sitting next to us on the train, the person ahead of us in line at a store who we might not have noticed before, the person who vaguely resembles a character in the story we’ve just read and for whom we have new compassion because we feel, in a mysterious way, that through that character we gained insight into some small part of humanity.

We like to recognize ourselves in stories, of course, but it’s equally important to read about characters utterly unlike ourselves, especially characters traditionally underrepresented in literature; they’re the same people who often don’t get a loud enough voice in life. Doing so takes us out of our world and brings us back to the world at large. And when we come to the last word of a story or a book, the gift is that we look up and see that the world beyond the page is deeper and more complex, more wide-ranging and more beautiful than it was before we started.

Cristina Henriquez's novel, The Book of Unknown Americans, is available on Amazon and with booksellers around the UK from Thursday.

- Luke Neima's blog

- Log in to post comments

- 3163 reads