Margot (Part 1 of 2)

By rosaliekempthorne

- 553 reads

My name is Margot. And my superpower is that I’m invisible.

It’s not as cool as it sounds, and it’s not that kind of invisible.

Well, nor is it as bad as I just implied. I didn’t come here to complain, or parade myself, or seek attention. I’m here because…

... because…

I think it’s because of Alex.

#

Alex is my brother. One of my brothers. Imagine growing up in the family that never ends, where there’s more siblings than you know what to do with, where you really do have trouble keeping count, and where only about half of them are related to you by blood or marriage or anything much more than circumstance.

So, let’s count them.

There’s the oldest: Lydia. She’s related to me and Dad, but not Mum. She came from his first marriage. She’s mean. Yeah, she’s the mean one. But I don’t want to sound harsh about it, because Lydia’s the best. She’s the wolf of the family. She could tear the little ones amongst us to shreds, but she always had our heart in hers. If she kept us in line, she kept us safe as well. Not quite like another mother. But she faced off any and all threats.

She faced off a grown man once. Lyddy was twelve, I was maybe five or six. I was too young to know what the dark side of the world really looked like. Monsters were for story books, but this one was right there, in bushes, between us and the road home. He was staggering drunk, with a bottle still in his hand, stomping out of the bushes like a fairytale giant. Poison in his eyes. His fiery breath causing us to shy away.

And he had it in for Bobby. No reason. No logic.

He was screaming at him, waving his bottle around, spitting out curses and telling this eight-year-old boy that he was going to hurt him like he’d never been hurt. Hurts him and me were too young to understand. Us youngsters clinging, cringing; while Lydia marched on up to him and stared him down. “You wanna try it on with my brother? Or do you want me to call down his dad, and his step-mum, and all my brothers and cousins, and the neighbour across the street who’s as mean as the both of his dogs? You want me go fetch all that lot?” Our Lyddy didn’t flinch. She didn’t turn away from the string of pounding words he poured on her. She showed her teeth; she squared her shoulders; she all-but snarled and growled.

That’s Lydia.

And then there’s Gordy. Same age as Lydia, but on Mum’s side of the family. The two of them were always rivals. The same strength in both of them, the same weaving-in of steel. Both kinda smart, both sporty. Both winners. No wonder then that they snapped at each other, that there were sparks and bonfires.

“If Mum and Dad weren’t married,” Alex told me, “you know they’d be going out.”

And then there’s the twins. Duncan and Jayden. Totally identical. Even to us who live with them, and Mum who pushed them out in the first place. They could be conjoined, might as well be, since they’re always together and they’re like carbon copies, and they finish each other’s sentences, come up with the same ideas. There’s just no way to separate them. Like they’re one entity. Really. And they play with us: which is which, which is which? – they trick us as much as they please. DunJay we call them. So we don’t have to worry about which one we’re talking to. As far as I know they don’t mind.

And Bobby. Related to nobody. Came to stay when there was just Dad. He showed up not long before Dad hooked up with Mum. And Dad swears and swears that no, Bobby’s not some by-blow from his chequered past. Whatever else is true, he never fathered that kid. But he acted as a father, from the moment he got him. Son of a friend, but that friend had made a horse’s arse of his life. He was in it up to his chin, and since he didn’t want his son to be just as deep in – Dad to the rescue. Dad his only chance.

At least Dad tells it that way, and refuses any other interpretation.

Then Alex. The sweet one. It’s not true that parents don’t play favourites. He was the first one that Mum and Dad had together. He was something that cemented their closeness. And his soul has always been gentle. The kid who gave the least trouble. Sensitive and bookish, in a family that was boisterous, tough, loud, outgoing. Our little introvert. And loved all the more for it.

And then along came me.

The very next year.

I was kind of a surprise. Although the way they were carrying on like rabbits back then – so Aunty Sophie tells us – I shouldn’t have been. And it wasn’t exactly as if Mum had other plans, or as if there just wasn’t the money to raise another child. It was just that there wasn’t the mindset, the ‘lets-have-a-baby.’ And so, I was a mixed blessing.

More so since this last child was slower than the rest. Not really slow, but lacking in the quick wit of the eldest ones, fussy compared to the soft-flowing moods of their Alex. And a big girl. Which the years saw only getting more pronounced. Not especially tall or especially fat – though I always knew I surpassed the average on both counts – but just big, broad, heavy-set. A big bumbling girl who couldn’t manage the art of belonging, and mastered instead of the art of hiding.

After me came Enid. The one who’s a little bit like me. Two-left-footed, but the left feet are of nearly normal size. Her teeth are crooked, and ears stick out, but she’s still a country mile prettiest out of us two.

Then Tara, who was a foster. Who started out as a foster, and sort of inflicted herself upon the family. Who was noisy and demanding and uncannily lovable. A mercurial thing who was a tomboy one day, little scholar another, wild-child, rock-star, princess as the mood took her. She came under our protection from a life that had involved endless moving, total unsettledness, a mother whose feet couldn’t grow roots, whose head was muddled with drugs and dreams.

And Ben. Who’s only six.

And Miriam – our Miri – who’s four and a half. Who belongs, technically, to one of Gordy’s friends – “she really doesn’t have anywhere else for her. The little girl’s cute, and Gretchen’s really, really in need here.”

And “Titch” whose real name is Tina. Two years old last week.

I’ve heard people say about my Dad: has he never heard of a condom?

#

I was fourteen that year Mum made me go to the dance.

I didn’t want to go, and I couldn’t see why she couldn’t see that it was only going to be tears and pain and a few extra doses of exclusion. But her friends’ girls were going, and Lydia had been the belle of the ball at that age. It was going to be good for me, that’s how Mum saw it, something to bring me out of that shell I’d spent half my life cultivating and was in no hurry what-so-ever to leave.

And she got to play dress-up.

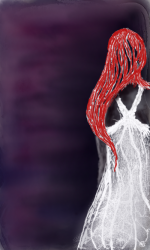

She took me out on the town, we got lunch. We tried on dresses. And I suppose I did my best, tried to be interested, tried not to cringe at what I saw in the mirror. She picked me out a lacy number, in white, all spider-webbed lace, filmy, so odd on me. I felt like Brienne from Game of Thrones: all decked out in the pink dress, tourney-sword in hand, psyching myself up to fight the bear.

Maybe that’s why I dyed my hair bright red. Why it made Mum cry. Why there was shrieking and recriminations on both sides. Everybody getting involved.

You can’t tell that from the photo. I stand in the photo quite demurely, with my hands clasped in front of me, white dress flowing calmly to my knees, the red-red hair combed back and managing to seem almost sedate. I gave the camera a shy little smile. All the crap whirling around in my head at the time doesn’t translate onto photo-paper: that could have been a happy, normal, almost-enthusiastic girl.

Broken crockery swept up and not in the shot.

And then the bear. The bear was just as big and grizzled as my imagination had feared. He was large, noisy, pulsing with lights and hard music. I could feel the bass vibrate along my sternum as I walked in the door. Alone. Because I didn’t really have any proper friends, and there’d been precious little chance of finding a date.

Girls in swish dresses. Girls in black, play-acting being twenty-five; play-acting being princesses, high-society models, actresses; indulging in their mothers’ permission to let them wear make-up for the night. Some of them had such an elegance about them, they almost could have been adult women. Some of them giggled like six-year-olds, and yet here, that was okay, that was part of the experience, and it didn’t make them sparkle any less. Boys pressed into suits, carnations in button-holes, stood looking slightly lost at the side, arm-linked but slightly perplexed. Really just wanting to make out with the girls, get them out the back and try their luck copping a feel.

The elephant in that room drank punch and sat alone against a wall. A wall-weed, since she was so unpetalled, and so aware of her unpetalled-ness. If it seems like the biggest slice of silliness now, then you have to remember that I was fourteen at the time, massively insecure, and tossed into a pool of sharks. I was the elephant-man in my own imagination, freak, yeti, abomination. My imagination got so caught up in this I felt tears sting the corners of my eyes.

I hardly knew his name at the time, but I’ll remember it now for a lifetime.

Darren Hunter.

He stood in front of me, actually extending his hand. Did I want to dance?

I didn’t. And yet. This prospect of actually being wanted. This sudden normalisation. You can’t help yourself. I stood, I let him take me out there. The top of his head came to the height of my eyes, and he danced with a kind of untroubled ease. Made me feel as if I could do the same. A Cinderella moment.

Until I heard them laughing. A bunch of witchy girls on the sidelines. Most of them beauties; popular, all piled together along the benches, with limbs overlapping, glitter-tights braided in the rainbow they’d selected between them. I heard snatches of my name, cruel, stabbing giggles. I saw them glance and duck in my direction. “Having a good time, Margot?”

And it would have been all right if Darren hadn’t been joining in. He was casting them conspiratorial grins, he was winking, he spent a few moments imitating the lumbering style of my dance. It might have gone on, but by then I’d lowered my arms, looking at him, trying to decide if I wanted to punch him. His grin wasn’t for me, it was directed internally: proud of himself, of this little display put on for everyone to laugh at my expense.

I left early. I caught the bus home. And I regret only the decision not to punch him in the face before I left.

I knew there’d be hell to pay later with Mum – running off, not calling, bailing. And when I told her why I’d left: all sympathy lined with recrimination: that the dance should have gone south like this for me and I hadn’t reached out to her. Why on earth hadn’t I just called her?

It was dark. Frost in the air. I kicked off my shoes and left them foundering in the grass while I wandered up to the oak in the back garden. I didn’t care if I ruined the dress clambering up into the old treehouse. But I did cry in silence. I cared more than I could describe that somebody might hear me.

Well, nobody did. But Alex found his way out there anyway. He insisted there had been nothing to guide him but silence, and yet, there he was at the bottom of the tree: “Permission to come aboard?”

“Oh, don’t. Don’t climb up here.”

But he did. Rolling himself onto the wooden platform and putting his arm around me.

Alex, he was different from the others. He was born with a sensitivity that just doesn’t run in our family. I found I could tell him the whole thing and not even feel like an idiot.

“What a pack of little shits,” he said.

But it must be me. It must be something I was or did, some vibe I gave off.

“They’re worthless. They really are.”

“Mum’ll go mental.”

“Huh. Maybe. Well, you didn’t want to go in the first place.”

Trying not to cry: “I really didn’t.”

“Dancing,” he said, as if with total sincerity. “Overrated anyway.”

I was such a bitch. You see, about Alex: he hasn’t had a normal life, or an easy life. His leg wasn’t functioning right since he was born. And then there were tumours in it when he was six or seven. Chunks removed. And it was swollen, like twice the size of a normal leg. Dancing was something he’d never get to do, dragging his leg around like it was filled with wet cement.

And I’d made him climb a tree.

“I love you,” I explained, out of the blue.

“Well, no shit. You’re like my favourite sister.”

And he meant it. And me: I promised myself to be a better sister to him, from that moment on, pretty much through adulthood, into old age. And I dedicated myself with more resolve than ever to perfecting my invisibility.

Picture credit/discredit: author's own work

- Log in to post comments

Comments

A great character that we can

A great character that we can relate to, lovely descriptions too.

- Log in to post comments

I like how you describe the

I like how you describe the disco as be like a bear. And that Margot dyed her red

- Log in to post comments