Life and Times of a Priestess: Ch.11: Dumis (Part 2 -Section1)

By Kurt Rellians

- 498 reads

Ch.11: Dumis

Part 2

Ravelleon took her to the opera on one occasion. This proved to be another tale of blighted love in which the political circumstances of the time stand in the way of the love of the two young lovers. Their families and civil war drove them apart at the height of their passion, and even, for a time, turned them away from each other. They found ways to forgive each other and to see each other illicitly. Eventually they were tricked into believing each other dead and through ridiculous blunders of misunderstanding they both take their own lives. Danella enjoyed the tale for the understanding it gave of the Prancirian concept of love and also for the beauty and serenity of the music which was unlike the musics of Pirion, in the size of the orchestra as well as the deep control of the singers. Music in Pirion was a far more casual affair although certainly enjoyable. These Prancirians however really put their backs and their brains into it, learning long and complex pieces from sheet music and long series of words, sometimes even sung in a foreign language, typically Spalopian or Vanmandrian.

The tale proved to Danella how ridiculous Vanmarian ‘love’ was. “The idea that anyone should kill themselves because they believe their lover to be dead is quite ridiculous,” she said to Ravelleon at the end. “Surely the Prancirians would never do such a thing. They may become upset when they lose their lovers. I have read and seen that in you jealous people, but to kill your yourselves …..”, her sentence petered out as she shook her head in horror. “Surely people don’t do that here?”

“Of course not”, said Ravelleon, “it’s only a story.”

“Then why do they kill themselves if it would never happen in real life?”

“It is to emphasise the love of two people for each other in the face of adversity. The story celebrates the triumph of love over the expectations of their families and the dissensions of their nation. It is not meant to be real. It represents the power of love,” defended Ravelleon.

“It represents the irrationality of your love, surely. I admit it was charming and if I suspend the knowledge of real life as I know it I can enjoy seeing them fight for their love against the rest of the world. But it celebrates the love of two people only. The other characters seem to have no love at all. There is no thought that anyone but the two lead characters should need any love. They are ignored as if they are not humans who need any love at all. Like all your Prancirian art you seem to enjoy observing young idealised lovers in your romantic love but you do not allow yourselves to have it too. There is no sharing of love. Love is jealously guarded. You all aspire to the perfection of love but very few of you ever achieve it. Your idealised love is false. You would all do well to appreciate something less perfect and to enjoy more peace in your lives.”

He encouraged her to indulge herself, to buy whatever she wanted. She did just that and took great pleasure in the shopping trips with Ravelleon and occasionally some of the new female friends he introduced her to. Some of them were very keen on the pleasures of shopping, to the extent that Danella, much as she had enjoyed shopping for the pretty clothes, became bored with their constant witterings about clothing and perfume and their frequent comparisons, drawn on the appearance of other ladies in the shopping streets. These ladies, whom Ravelleon knew, were the wives of other Generals or high officers in the army, or of important company directors or government officials and politicians. He knew them through the social gatherings of the rich and famous, which were so important to him because of the powerful contacts he made. These contacts had proved essential to him in his rise to prominence in the army as a General, and in the national circles of power as a figure of influence on the government, and also amongst the big business figures of power brokers who could so influence government policies and spread his own reputation.

Some of the women were shallow creatures, concerned mainly with their own husbands and families, and their ‘position’ in the hierarchy of society. She was quite sure these women had selected their husbands not merely for their Vanmarian ‘love’, but also on the grounds of their status in the nation and the amounts of money held in their bank accounts and in the value of the possessions. They thought little about the wider world, and certainly little about the justice of that ‘little’ war in a continent which they believed to be far distant and of little consequence to them. Danella found them pleasant and friendly to her at first. Some of them were quite lonely for male company, as their husbands, particularly the army ones but also some of the politician’s and director’s wives, were away for long periods. Their sexual abandonment left them plenty of time for other social pastimes in which most socialised with their fellow women, idling their time away in pleasant and flippant conversations, endless shopping expeditions and the evening social events, dances, dinners, operas, ballets, concerts, plays and card games where they went often with their husbands if they were available, but with groups of similar women occasionally if they were not. Sometimes they would mix with the other men and their wives of their social circle even if their husbands were not present, at the social events. Thus Danella was not out of place when she sometimes went with them.

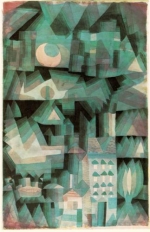

These people, these proud Prancirians lived in fear. The women were afraid of their husbands. The husbands were afraid of their wives. Most of all they were all afraid of their employers. Fear of losing their jobs drove them to depths of subservience, which the relaxed citizens of Pirion would have found incredible. They were afraid of the war, afraid of sex, afraid of their neighbours, afraid of the truth. Their reaction to fear was conformity to what they felt was expected of them. This led the men and ordinary people to work long hours often for meagre pay, and to live drab unfulfilled lives. Their hopes and dreams were expressed in analogies, in paintings and pictures, in books, in theatres, music halls and musicals. These parts of their culture were indeed rich, but in the enactment’s of this culture they often expressed the lies and suppression which their lives were based on. The culture expressed something of what they all wanted, but it refused to go all the way and reveal their complete desires. Their culture stopped short of demanding that their desires were turned into realities. Instead they parodied the desires and made them seem childish or immature, or the mistakes and fantasies of weaklings.

Sexual desiring was everywhere in the arts of Prancir and of the other nations of Vanmar which she had seen, for at some times in its history Prancirian conquerors had pillaged, or its wealthy power mongers had purchased from the defeated and the desperate great works of art from those other nations, paintings, statues, even obelisks and parts of foreign temples. These they had placed in their many art galleries and museums, mainly in their capital Dumis although also were many hidden away in the private collections of old aristocrats and the new made wealthy alike. Sexual desire could be seen in the paintings of ancient tales and of religious stories alike. The artists had used the freedom unleashed by the distance of past and legend to breath erotic life into them. The denizens of the cruellest Empires of the past which had once held sway over Vanmar and the coasts of the Middle Sea were depicted as wearing gowns and togas, which even for men as well as women had a tendency to slip gently from the shoulders, revealing the occasional well placed nipple or the sight of well carved flesh on the leg or buttock. Artists of the past and even of the present seemed to have a fascination for these ancient and half mythical periods. They were times on which ancient Charlendane, and the more recent Chameleon, had based the imagery of their regimes, harking back to a golden age which Danella observed was hardly golden for its many victims.

Even the religious paintings, evoking the origins of Vanmar’s old religion which had been, Danella understood from Ravelleon’s friend Mireau, partly responsible for the current attitudes of limiting sexuality, and the culture of abstinence in which so many Vanmarians were enslaved. Even these contained the beauty of the female characters and of the males, the attention to the shape and to the beauty of the bodies. Danella had the sense that the artists might have been denied the fullness of sexual freedom, but they could very well appreciate what they could not enjoy physically and took every opportunity to worship the female and the male form.

- Log in to post comments