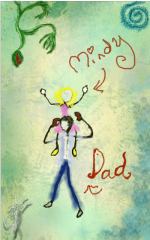

Mindy Unsworth: Some Words About my Father

By rosaliekempthorne

- 551 reads

My father.

Well, you can't choose 'em. Isn't that what they say?

But don't get me wrong. I would. Almost always.

More often than not.

#

If my mother faced a challenge when she had me, my father faced two of them. Me and her. Both of us a little bit mad in our own way. Peas in a pod. Him, the square peg trying to squeeze into too many round holes.

When you see my father, you think: wow, that's a regular guy; puts his trousers on one leg at a time, drinks a few beers, goes to the footy, goes down to the pub when it's done. A faded blue shirt worn open over a white singlet. Loose jeans, smudged with grease and dirt. He's gotten a little bit rounder over the years – I've seen the photos that show me a whole other image – a little bit less well-thatched up top.

He wears glasses when no-one can see him.

He watches sad movies with Mum sometimes – in some secret night-time with the lights off and the colours of the TV screen lighting up a small, ragged couch. Striped wallpaper and snow-globes lining a shelf right behind them. He'd deny it to any of his friends, and he'd deny twice as hard that he kind of likes it. I'd watch them when I was little – them, the movies; from the hallway, through a crack in the door. Him with his arm around her, while she tucked herself into his looming, familiar shape; while she buried a hand in his lap, and her head beneath his shoulder. I was so young I thought they lived in perfect, tranquil happiness.

For years and years I measured love by that image.

#

My father delivers the post. He gets up in the dark. He kisses my mother without quite properly waking her, brushing her cheek with an upper lip and the edge of front tooth. And I'll hear him making his way down the stairs, picking up his mailbags, pulling on his boots and raincoat. It might be hailing out there, or the roads might be glacial-white with frost. I've never heard him turn back and say “no way” or “screw this.” But I've sometimes heard him humming to himself as he leaves.

When I was young, I didn't know the tune.

It's “Walking on Sunshine” and he hums it in the rain as he walks down the garden path.

#

My father.

Dad.

He brings his friends over every other week. Sometimes it's to watch a game, but mostly they're up drinking beer and playing cards. They're a rough, ragged, free-swearing crew. They were the ones to teach me words beginning with 'f' and 'c', ten years or so too early to hear that kind of thing. Conversation always turned to subjects too old and rough for my ears: to sex, drinking, some fight that happened last night down at the pub.

Great guys though. Barney: the hard man. The don't-cross-me guy. Full of attitude. Full of swagger. A mean side. But I've never seen the business end of it; not since he first started coming over, and I was a little blond-topped toddler in bare feet and ribbons. More welcome on his lap most nights than Dad's. Dad: always focussed on the game, the chips, some rant or other – the wrong time for small children. His time. But Barney: holding his arms up, inviting me up there, letting me see his hands, seeking my silly six-year-old advice. And me always giving it.

And Rick. The respectable one. The one who works in an office. The one I knew at first for a monster, the first day I met him, walking into our hallway green-faced and dripping slime. His voice having an echo that made the walls shiver. At least for me. It's taken time for me to see a red-haired, middle-aged, ordinary guy. To see his hidden bloodline and then quickly not see it.

And Lance. And Martin. And Redmond – now there's a name to haunt a kid through high school. And Jack.

You know, I don't think Dad ever asked me to call them Mr Such-and-such: it was first names the whole way, for as long as I can remember. Because Dad really doesn't have much patience with that whole idea of respecting your elders. Respect them for what they do, for how much bigger they are than you, and for the size of their fists. And for how half-decent they are. Grey hairs and years lived are beside the point in his book. And fair's fair: he hasn't changed his feelings as his own hairs lighten and daily disappear.

Poor Grandad. A surly, sulky youth on his hands. An absolute believer in his equality with his father. But then Grandad, he thought along the same lines. For better or worse he friend-parented, he sat Dad along side him. They could talk one-on-one, equal footings, man to man. For as long as my Dad can remember.

Some things run in families.

#

And so, anyway, the cards come out. They bet real money.

Mum makes them chips in the oven, puts salsa and cheese on them, and brings them out to the table every hour or so. She never seems to get tired of it, even when it's late. But then they flirt with her and make her feel young. They tease her over her flighty ways and insist that Dad doesn't deserve her. “Come home with me, Kara, I'd make you a proper husband.”

“Don't tempt me, Jack. I might do it.”

He's seen her dance.

Dad's seen him see it. So sometimes, after dark, there's recriminations following: “Why do you flirt with them like that? Embarrrassing me. Making them think things.”

Her. Her answer: “Those are your friends.”

#

He does have a temper on him.

My father.

He doesn't much turn it on us, but I've seen him when he thinks he's been wronged. There was a time when we went up north, on holiday, when we were staying at a caravan park. We had a place rented, and we'd gone out for the day, only to come back and find it rented out to some other family.

So this is how I remember Dad: he was standing there in reception, banging his fist against the desk, he was demanding that they chuck that other family out, give him back what was his. No, he didn't care that this was just a clerical error. No, he didn't want to hear them apologise and offer another caravan.

“We don't mind-” Mum started to say.

“Oh, we do mind. We do mind. We do mind!” He was thumping his fist over and over again on that desk, making all the little ornaments and pens shake. There was this animal thread in the sound of his voice, shouting that was on the verge of snarling, on the verge of becoming a wolf's voices, a bear's voice, not a man's. And I know that I saw mist swirling around him, dark and cocooning, billowing out of his pores. I was nine and I was me: I wondered if he was going to transform – hair and teeth and claws – and I wondered what I was going to do if he did.

Out into the camping ground, yanking open a door. Ordering a couple of strangers out of a rented caravan. He was all mouth and fists. All threat. He had the guy dragged down a couple of steps and was pushing him backwards along the grass. Shove. Charge. Shove. Charge. A red-haired, pale-faced wife intervened. When Dad turned on her I saw her eyes change, I saw her courage leaking out of her. As if she were melting.

And Mum: “You lay a hand on her and I'll lay a hand on you. You know I will.”

“No loyalty.” “What sort of a bloody wife...?”

But that family stayed in their caravan. We: leaving before the cops got there. Never going back again.

#

But look. He tries. He does his best to understand me. And it's not always easy.

Here's an example: he asked me once about the unicorn I was drawing – this thing that looked nothing like the white, pristine, spiral-horned equine you see in fairy stories. He ventured that he didn't know unicorns looked quite like that. Was I sure that's what it was?

And how could he know, just a few feet away from it, that the very same unicorn looking right at him through our window? A stocky, muscled thing, as grey as white, with that crystalline shine to it that unicorns have. Teeth like sharpened bricks. Its blue eyes and mine were deadlocked, full of warning for each other, sizing each other up.

“He got a name?” Dad asked of my unicorn-on-paper.

“I don't think so,” I murmured, squeezing a little bit of starfire into my palm, letting it sparkle and burn, warning that unicorn not to come any closer.

“You're an oddity aren't you, Mindy?”

Aged seven: “What does oddity mean?”

“Something strange. Something different. Something that doesn't quite fit.”

Some kids might've been hurt or upset by that. I just thought that it fit me like a glove. I'm an hexagonal peg – with little spikes coming off me, bulges, crooked edges - in a world full of tame and orderly round holes. Or so I like to think of myself.

Ego problem, much?

But if I'm an oddity out in the world, then he's an oddity here in this house. A tortoise in a cage with two tropical birds. Bright colours to his black. Clouds to his clods of earth. Or am I overselling this a bit?

#

Well, it's not easy for him. He's not a guy who's good with words. He would probably like to say all the right things: to tell me I'm pretty, or good, or that he's proud of me for getting good marks at school or something (in the event that ever happens.) He just doesn't have the vocabulary. The words “I love you” don't make an appearance in his dictionary. Mum's learnt to live with it, so I can too.

He'll joke instead of praise. Brush-off instead of comfort.

I've learnt not to go to him crying if I'm scared. I've learnt not to let him see tears. “You're not a baby, Mindy. You can't get upset over every little thing. You gotta be tough.”

“Just a scratch, Mindy.”

Not ever, any kissing of it better.

But he shows it sometimes: a surprise gift, a confidence, a trip to the races, or a too-fast drive in the car. Sometimes it's just the look that he'll get in his eye when he thinks I don't see him, this odd

mixture of pride and mild confusion. So I know – words notwithstanding – that he loves me just plenty.

#

He was a looker in the old days. My father.

Like I say, I've seen the photographic evidence. He had that laid-back, easy-going aura that draws the girls in. He was dark around the eyes, while his hair evidenced a mid-brown, just touched with a frosting of sunny gold. A long face. A strong jawline.

Photographed: in a red jacket, leaning against a park bench, hands in pockets, wind catching a bit of mid-long hair. Looking like he was laughing.

I can see why Mum went for him.

#

When I was young - and this is maybe four or five - no older than six - my father would take me out with him. We'd go down to the river and I'd watch him fish. Or he'd teach me to swim. We might just sit there skimming stones and looking for fish. I'd squeal if I saw one, getting so excited. He taught me to high-five. He taught me to tie knots and find worms. He taught me the best fart jokes I know – even today.

And as I got older, he'd tell me things about boys – what he told me my mother didn't know. Never mind that she'd told me all the same things. And: “You come to me if he hurts you. If he gets handsy. I'll put those hands back in his pockets for him.”

“Dad!”

“No. I will.”

And he did. But that's another story.

#

And this: four or five again. My father still played soccer then. He was still in a team. They wore blue and maroon striped shirts, and they'd play every Saturday afternoon. In the morning we'd go down to the local park, where they'd practice. I'd always be along. He'd put me up on his shoulders, running and kicking with me hanging on by my knees. I was like an extension of his flesh, and he'd half-forget I was there, charging into a tackle for the ball, going for a header or taking the ball on his chest without a thought for the squealing, laughing, red-faced creature on his shoulders.

And me, mini-me, I felt so alive. I was a head higher than anyone - Princess of Half the Earth - and my face was aching from smiling, my skin chapped and singing, my hair flapping all over my face in the wind.

After the game we'd go to the club. The men would drink beer. Dad would buy me a coke and some salt-and-vinegar chips. All would be smoky and convivial.

I knew I was his absolutely favourite girl in the world.

- Log in to post comments