The Shellsuit

By Caldwell

- 55 reads

All my adult life, I’ve carried a complicated relationship with my father. At first, I thought the solution was distance—emotional, then physical. I moved abroad, partly to escape the quiet claustrophobia of family obligations and dynamics I couldn’t seem to untangle. It gave me the perfect excuse to decline invitations or to soften the sting of not receiving them. Recently, a dream brought my father back to me—not as the man he was, but as someone freer, unfamiliar, and somehow more real. This piece came from that dream.

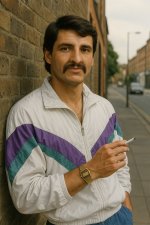

The dream came without warning, as they often do. I was walking down a South London street, near The Oval. The air was thick with that familiar city hum—traffic, voices, fragments of life moving in all directions. As I crossed the road, I noticed a man leaning casually against a wall. One knee bent, cigarette in hand, he wore a white shellsuit streaked with purple and green. A gold Casio watch caught the low sun. A chain glinted around his neck. A decent, thick black mustache. There was something so complete, so self-contained about him.

Then I recognised him. It was Dad.

But not the man I knew from childhood—the antiques dealer in tweed and corduroy, the Mercedes-driving chairman of Rotary meetings in Surrey. This man was different. He was my age—forty, give or take. He looked good. Healthy, even lithe. An entrepreneur of some kind, I imagined. Not the man I grew up watching, but a parallel version—my contemporary, not my elder. Someone I might pass on the street and size up with curiosity, not filial duty.

When I passed, I nodded and told him he was looking great. He nodded back. Just a flicker—a flash of appreciation. And then I walked on. But something inside me swelled. I felt proud of him.

In waking life, that feeling stuck with me. The pride, the recognition. The sense that this version of him was free. That he had finally stepped out of the role he had worn so comfortably—too comfortably, I always thought. The tweed jackets, the cordial smiles, the antiques with their smell of beeswax and worn mahogany—all part of a performance he rarely broke from. I used to wish, when he went on probate valuations, that he was secretly having an affair or even affairs plural: That he had some secret, some passion burning underneath. A double life would have made sense - something to take the edge off his predictable routine, suffocating comfort - heating on too high with thick carpets and heavy curtains. The acrid waft of stale tea, roast after roast coming out of the oven and accompanied by too much wine - so generous, so happy in this mundane jigsaw of dull content. But no. He remained faithful, constant, and frustratingly boring. I couldn’t understand it. It disappointed me.

After the dream, I went to a couple of thrift shops. I tried on real shellsuits—genuine vintage, zips and swishes and all. But they didn’t fit. Not physically, not emotionally. It felt like a costume, a masquerade. A look that belonged to someone else.

And then it struck me. That was the point. This version of my father, the one in the dream, was never meant to become me. He was an image, a possibility, a symbol of the unlived life. As the closest living echo of him now, I think I believed I had a responsibility to carry him where he hadn’t dared go. To live the wildness he hadn’t touched. But my story—it’s my own. It doesn't follow his path, not even the one I wished he’d taken.

Still, I felt pride. Not for what he was, but for what I imagined he could be. That feeling, however dream-born, was real. And maybe that’s enough. Not to fix the past or become what he wasn’t, but to recognise those imagined versions and let them inform my own journey—as a kind of compass, not a blueprint.

Some dreams ask us to act. Others simply ask us to notice. This one did both.

- Log in to post comments