Dawn

By Sven

- 3713 reads

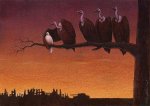

Dawn

By Richard Geneva

The whistles are terrible at dawn. They announce the beginning of yet another day of slaughter. Often, I lay among the broken sandbags in the bottom of the ditch just simply aching with fatigue. Broken dreams and broken sleep, and never are the nights long enough in which to rest before the stand to at dawn.

The morning mist curls and billows among the wire as I look across no man’s land towards the German positions. Yesterday they dropped leaflets on our lines. It showed rows of skeletons laid in straight lines awaiting burial, dressed in British uniform. It is difficult to say what effect this had on some of the younger ones, especially those fresh from ‘Blighty,' who have read the headlines of leading tabloids and believed we were bathing ourselves in glory when the only bathing around here is in the blood of the dead and dying.

I am tired. We are all tired, but I try to keep frisky in front of the men, try to strike a note of irreverence as if mocking the mere notion of hooded figures with scythes that march alongside us in our nightmares.

I steady my hand and look once more through the tangled wire. I see ghostly apparitions of fallen comrades. Tommy Atkins and Billy Williams are walking towards me side-by-side; yet in yesterday’s advance, I'm sure they died. They died in the first German bombardment. I saw them fall in the hail of shrapnel that ripped through the assembled ranks, as we marched slowly forward.

I looked in the cracked mirror on the wall of the underground bunker earlier and hardly recognised the rheumy red eyes staring back at me. It has been several days now since last, we slept, and I desperately sought refuge from the noise of the big guns that have been firing over our position from the rear for several days. It is the prelude to our advance towards Ypres. It is the brainchild of no less a person than General Sir Douglas Haig, and General Gough himself is leading it. I remember ‘Grouchy’ from Sandhurst, where he was a staff officer when I was taking my commission, an absolute ‘bounder’ of the first degree.

I return to the letter I’m writing. “…I think of you now Tamara, in these few precious moments before the battle. How we would sit by the fire with the children and read aloud to them, and they would sing songs they had known since babyhood. I remember our last evening together. How we talked, and cried, and loved, and then we fell asleep in each other’s arms, has the cold reflected light of the snow, crept through the frost-covered windows.

I remember the thick mist; it hung everywhere, on that morning. There was no sound except, far away in the valley, a train shunting. I stood at the gate and waved goodbye and kept turning and waving until the mist hid you from view. Then through the muffled air came your voice, your old calls coming after me "Coo-ee."

And like an echo, I called "Coo-ee" keeping my voice strong to call again. "Coo-ee"

You are so faint now, so far away.

Now, there is nothing except the silence of the grave…

All night it’s rained. The jolly old rain. Prolonged sweeping rain that hammers on the sheet metal supporting the sides of the trenches and runs in small rivers down the sides. We live in mud, and we die in mud, "Nothing quite like it for cooling the blood."

My fellow officers lie around the dugout and talk in low whispers. Overhead, shells scream towards the German positions a mile or so in front. Nobody is quite sure when we will have to rise from our trenches and summon the demoralised men forward into battle. It is a heart-breaking prospect.

Already we have been forward and inspected the open fields through which we must go. Already we have witnessed the killing that German machine guns inflict among our fellow troops. We have heard the screams, and seen the rotting dead, wallowing faces, in the sucking mud. Now we talk in nervous whispers. All bravado’s gone, and we are alone with our thoughts.

A cold shiver runs down my spine. I wrap my Greatcoat around me and strap my pistol to my side. Soon it will be time. I go outside once more.

"Good morning sir," whispers Corporal Plunkett.

"Morning Plunkett, anything to report."

"No, sir. It seems the bombardment is keeping their heads down."

I stand in the trench ankle-deep in mud and look through the eyeholes of the periscope towards the German positions. Low drooping flares confuse my memory of the salient. I realise our big guns have now stopped. I stand on a box so I can look above the parapet with binoculars.

Towards the east, the misery of dawn begins to grow, and a fierce iced wind blows through the trenches. Now the silence worries us all. We stand to once more, wait in the grey light, and watch the clouds sag stormy across the sky. Bayonets get fixed to rifles, steel against steel, and hardly a whisper.

The rain and wind blow, on our upturned dreaming faces, and I rub my hands together in almost silent prayer, and command an end to this slaughter, and pray to God that he absolves us all from the murder we must commit.

Now the whistles blow, and we rise from our crouched position and start scrambling over the top of the trenches. Attacking once more in ranks of shivering grey, we march out into the dawn: a melancholy army.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

I guess we'll never know how

I guess we'll never know how bad it was being there, but we can guess.

- Log in to post comments

Well imagined and very real.

Well imagined and very real.

- Log in to post comments