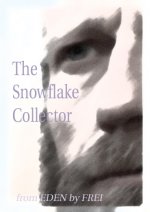

The Snowflake Collector – 1: Barely the End of October

By FREI

- 1561 reads

Up at the end of the valley, the far end, before it yields to the glacier which reaches down from the mountain pass, slowly receding now with growing temperatures, lives an old man who looks at the world still with wonder.

He is not as old as he seems at first glance and much older than his years nonetheless, for he knows. He knows, deep inside, what holds the universe together and what tears it apart and what being these molecules, what being that energy means. He knows it but he can’t express it and so he won’t. He won’t talk about it, he won’t, in fact, talk about anything much, he appreciates silence.

When he was young he used to meet up with friends for a drink and a chinwag and then it began to dawn on him that much of what he was being told and even more of what he heard himself speak was an array of variations on themes: things he’d heard said and had spoken before, in this way, or another. Self-sustaining iterations and reiterations of what everybody already knew and either keenly agreed on, or hotly disputed, as was their whim.

And so he let go, he let go of his friends whom he loved but could no longer bring himself to like, and let go of the circuitous conversations that did nothing but remind everybody that they were still who they thought they needed to want to be. He was tired, and being tired he got old, older than his years, older than his looks, older than the oak tree in the oldest garden. And he moved, once or twice first, then twice or thrice more, and each move took him further away from those whom he had been, had made himself feel, acquainted with. First the country, then the coast, then the foreign lands, then mountains, then the valley and then the end of the valley, in the mountains again. The remotest place he could find.

It was not that he was happy here, it was just that he was content. Content not to need to desire happiness any more. And here he sat and walked. Sat by the house he’d bought for very little, and walked over the fields and the meadows and up to the vantage points from which he could see the peaks and the woods and the villages, in the very great distance. He liked that distance: distance was space, distance was calm, distance was perspective. Distance was unencumberedness. It was good.

Winter came to the valley and it was barely the end of October and going for walks now was harder because everything was covered in snow. And this being the far end of the remotest valley he could find, nobody came to clear the snow or pave the paths or even the lane that led up to his hut. So he was stuck, in a way, and he liked being stuck, it meant, in a way, being safe. Safe from visitors, safe from the desire to go out, safe from choices. The persistent demand of decisions, abjured. Simplicity. He’d craved that. And now, he had it. What he was able to do still was sit on the bench in front of his hut and watch the world go by. Except the world didn’t go by here, it stood pretty much still. Or so it would seem. And he knew, of course, that this wasn’t true, that nothing stood still, that everything was in motion, always. He found it comforting. Disconcerting too, but comforting, and he’d said so. He’d said so and had been quoted as saying so too, and not long ago...

With each day that passed, winter became more present and more unreal. The snowflakes tumbling from the skies like clumsy, half-frozen bumble bees out of a freezer up in the cloud. There was something in him still that reminded him of the kindness of people and he let one or two of these snowflakes alight on his hand and they melted and ceased to exist. How sad, he thought to himself, how just and, yes, how poetic. And he recalled once upon a time being a poet and that’s when he decided to capture and keep them. Not all of them, obviously, only some. And to collect them. To preserve them. He knew this was futile and went against nature, but therein exactly lay the exquisite sensation of thrill and deep satisfaction. To do something that was futile and that went against nature, but that would be indescribably beautiful. That was more than existing, that went beyond breathing and eating and sleeping and defecating and shaking in anger and dreaming and imagining and sitting and thinking: that was living. That was imbuing the accidental presence in this constellation of clusters of mass-manifest energy with something that surpassed everything, something divine, something purposeful and profound, something quintessentially and incomparably human: meaning.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Welcome to ABCtales.

Hi FREI,

This is a good start. I like this old man and this life apart from things. The way you have drawn him invests a character that knows much more and much less than others might give him credit for. I love his setting and the vista that you've put him in. Just a couple of points if I may?

At the start just describe the glacier as 'shrinking' there's no need to nod towards global warming your readers will get it. The image of the snow as bumble bees is really effective but I think that describing their genesis as being from a freezer up in the clouds is at odds with the otherwise lyrical atmosphere you have worked hard to successfully create.

- Log in to post comments