Kari's Clan - 4

By jeand

- 2036 reads

“Shall we go on to read another one?” Berte asked Kari.

“Let’s have a break and you can go down and bring up the coffee. Did you bring any cake with you today?”

“I always bring something. This time it is krumkaker (which in English is rolled wafers, I think) that I helped Agnes and Mary make.”

“Will they be good cooks do you think?”

“They are very attentive and have a light hand. I am sure they will.”

After the break, there was only time for one more letter before Berte had to leave to make her way home, as this one was very long.

January 24, 1850

Dear family,

You have often mentioned in your letters to me, worries about the American Indians who might be living in this area. Let me tell you, there is no need for concern. The last big battle with Indians that

took place in Wisconsin finished on August 2, 1832. Here is a bit about the war, which was called the Black Hawk War.

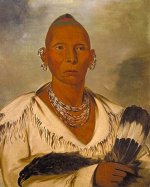

In the early 1800s the Sauk and Fox Indians lived along the Mississippi River from northwestern Illinois to southwestern Wisconsin. The Sauk leader was called Black Sparrow Hawk (pictured above).

In 1830, seeking to make way for settlers moving into Illinois, the United States required the Sauk to move and accept new lands in present-day Iowa (southwest from here). There they struggled to

prepare enough acreage for their crops. The winter of 1831-1832 was extremely difficult. In April 1832, Black Hawk led about one thousand Sauk and Fox people back to northern Illinois. He hoped to forge a military alliance with the Winnebago and other tribes. They intended to plant corn on their ancestral farmland. Fearing the Sauk, Illinois settlers promptly organized a militia. Observing the

military forces organizing against him, Black Hawk reconsidered his actions and decided to surrender. Yet an undisciplined militia ignored a peace flag and attacked the Sauk. The Indian warriors promptly returned fire. The militia retreated in a panic, many forgetting their firearms. The Sauk collected the weapons and retreated northward along the Rock River into Wisconsin.(That is near here.) The Black Hawk War had begun.

The army had four thousand militiamen. Traveling with small children and elderly members of the tribe, the Indians were unable to move as rapidly as the soldiers. In an effort to distract the Americans, warriors raided frontier farms and villages. On July 21, 1832, soldiers led by Henry Dodge caught up with Black Hawk's band near the Wisconsin River. Although greatly outnumbered, Sauk warriors turned the attack on American troops, allowing the Indian women and children to flee across the Wisconsin River. The next morning, the American troops discovered that the Sauk warriors had vanished, having quietly forded the river in darkness. Dodge subsequently fell back,

journeying north to Fort Winnebago to obtain supplies.

At Fort Winnebago, Dodge joined forces with Atkinson and set out in pursuit of the Sauk and Fox. Most members of the starving band had fled west, hoping to find sanctuary among tribes beyond the Mississippi River.

On August 2, U.S. soldiers attacked the Indians as they attempted to ford the Mississippi River. Ignoring a truce flag, the troops aboard a river steamboat fired cannons and rifles, killing hundreds,

including many children. Many of those who made it across the river were slain by the Eastern Sioux, allies of the Americans in 1832. Only 150 of the one thousand members of Black Hawk's band survived the events of that summer and those settled back in Iowa.

Black Hawk surrendered to officials at Fort Crawford, Prairie du Chine. The defeated warrior was imprisoned and sent east to meet with President Andrew Jackson and other government officials. Eventually the U. S. government sent him to live with surviving members of the Sauk and Fox nation.

So you see, the Indians who were here, who were not deemed dangerous anyway, were forced to leave this area. I have not seen any at all in my time here.

Your brother.

Ole

January 28, 1906

Now that a reason for her going had been established, and now that Kari had warmed to her sufficiently to be polite, Berte herself was intrigued about the letters, as her own experiences of coming to America, in 1888, had been quite different. The ship had been much faster, and the train journey had taken no more than three days.

It had become an established routine. Each Wednesday, Berte walked to Kari’s house, greeted the family, and then climbed the stairs and knocked on Kari’s door.

But now, instead of resentment, she was greeted with smiles and good humor. Kari herself had improved physically enough to be able to hobble around the room a bit, although she had not yet made the effort of trying to go down stairs. And her mood, instead of being depressed and self-pitying had changed to one of slight optimism.

When she and Berte together opened the box each Wednesday afternoon, it was with great wonder that they took out and read each and every one of Ole’s letters up until the pile wrapped in the pink ribbon was completely read.

“What should we read now?” Berte asked Kari. “Do you want me to open another pile, or shall we go through some of the pictures?”

“Let’s do pictures. I think they are in another box,” said Kari.

So lifting out the top shelf of the trunk, they found several boxes, each with a label. The first one Berte picked out had written on the top - 1851.

“What happened in 1851?” she asked.

“That’s when my family and I emigrated,” said Kari.

“And was your trip similar to your brother’s?”

“No, not at all. It was a dreadful trip from start to finish. But before I tell you about the trip, perhaps I should fill you in on the background of where we lived. In our part of Norway, several households – some related to each other and others not - all lived on one farm. It would be the landowner's household. (Ours, called Kjorstad, was my father’s initially, but when he died, it was taken over by my eldest brother, Thrond.) Then there were the household of tenant farmers, including my husband and me, renting parcels of the farm, and the households of sharecroppers who worked the land the

owner retained. In addition, servants, day laborers, and some paupers lived on most farms. All told, on a large farm, this could easily add up to 80 to 100 people living in a dozen separate households. Is that the sort of place where you were raised?”

“No, we lived in the town,” said Berte.

“Well,” went on Kari, “with 40 acres being the size of a large farm in Norway at that time it’s not hard to imagine the attraction that buying a similar size or much larger piece of land in Wisconsin for just one family would have had for us. To us coming here was like going to paradise. We so looked forward to it.”

“Here, let me see those photos,” and she took out a very faded picture of a tall, handsome young man. “This was my first husband, Ole. He was Knud’s father.”

“He looks very uncomfortable at having his picture taken.”

“It was very new in those days, and we were amongst the first in the village to have our photos taken. You had to stay still for ever such a long time.”

“So tell me about your awful journey. In what way did it differ?”

Kari seemed lost in a haze of her own imagining and didn’t really answer the question.

“We were so excited about our trip. My brother’s letters were so very encouraging, and we’d saved as hard as we could in order to afford the trip. There were four of us in the family - my husband, Ole, who was 35, I was 30 at the time, and we had our two young sons, Ole, who was six and Knud who was only a year old. Our boat, The "Christiane" departed from Drammen, Norway on May 17. After

an ocean voyage of eight weeks, we landed in New York City on July 10, 1851.”

“So you’ve lived here longer than you lived in Norway,” said Berte, stating the obvious. Kari ignored her remark and went on.

“My brother and his family and a few of our neighbors wrote long and glorious letters home describing the privileges and with what ease a poor man could provide for himself and family here in America so quite a crowd of us had decided to go. We sold all our household goods at an auction and the 12th of May we left our old home for Drammen, a city on the seacoast where we arrived the next day.

“The time of which I speak, 1851, was before steamboats, as you would have come in, were built large enough to cross the Atlantic, so consequently sailing vessels were the only conveyance used in those days for so long a voyage. As the wind was so very uncertain a power to propel a ship, its speed and the time it would take to make a trip from Norway to America could not with any certainty be estimated; and for that reason we stayed in Drammen almost a week and laid in a supply of provisions enough to last about three months so that we should not be in want in case of contrary wind and weather.

“The vessel in which we were to sail was a three masted brig large enough to accommodate 251 passengers. All these had registered from here and there all over the country and were getting their baggage and stuff aboard the vessel and stored away, making everything ready for the journey, so that May 17th, the anchor was hauled in, the sails were spread, and we glided down the Fjord of Drammen into the North Sea, and left old Norway behind until at last it looked like a dim cloud in the distance.”

“Were you sad to see it go?”

“Here, this is a photo of Valdres, and our land.”

Berte looked at it, and remarked how beautiful it looked.

“Beautiful yes, and we were sad as we knew we would never see it again, but we were so excited about our new life, that we’d no real regrets. And we knew that most of our family would be coming over as well, so the parting from them was only temporary.”

“The tall mountains of Norway were scarcely out of sight before men, women and children began to hunt their berths; the discomfort of a very severe attack of seasickness was more than the most of them could stand. The intention of our captain was to sail through the English Channel, but then about half way across the North Sea, the wind turned square against us, so we turned to the right and went through by the Shetland Islands and sailed half way around England and Ireland.

“After the first few days, the sea went calm, and we all settled in for a long journey, thinking it might not be too difficult after all. My job, of course, as well as looking after the boys, was to provide the

food.”

“What did you cook?” asked Berte. “We had food served to us on our boat.”

“If you would just be patient, and let me get on with my story,” said Kari with some of her old frustration creeping into her voice.

“The kitchen where the cooking was done for the passengers was a board shanty about 12 by 16 feet in size and was built on deck near the middle of the ship; along the back side of this shanty a box or rather a bin was built about 4 feet wide and about 1 1/2 feet high, and this bin was filled full of sand, and on top of this sand the fires were built and the cooking done. The kettles were set on top of a little triangular frame of iron with three short legs under it, and this people would set anywhere on this bed of sand where they could possibly find or squeeze out room and then start their fire

underneath. There was no chimney where the smoke could escape, only an opening in the roof the width of a board over the fire where smoke could go if it wanted to, but most of the time it did not want to because the wind kept it down.

“Then every morning at seven, Ole had to go down into the bottom room or hold of the vessel where the food and water was dealt out to each family for the day. The wood had to be split very fine before it could used to any advantage, and the water had to be put into jugs or something similar to prevent it from spilling.

“And now for the kitchen. Early in the morning you could see us women coming up from below with a little bundle of fine split wood in one hand and a little kettle of some kind or a coffee pot in the other, heading for the kitchen, eager to find a vacant place somewhere on this bed of sand large enough to set their kettle on and build a fire under it. But it would not be very late in the day, if the weather was favorable, till every place in the kitchen was occupied, and there would be a large crowd outside waiting for the next vacant place. Then imagine an oncoming big wave striking the vessel and almost setting it on end, and in a wink of an eye every kettle, coffee pot, and teapot is upset and spilled in the fire and hot ashes.

“But then our son, Ole got sick.”

“I don’t remember Knud ever mentioning that he had an older brother.”

“He died. He died of cholera on that awful awful journey. And he was buried at sea.” Kari started crying. Berte went up to her and awkwardly tried to put her arm around her, but was brushed away.

“Oh, I’m so sorry. I didn’t mean to bring up such sad memories for you. That must have been awful.”

“I will never forget the funeral. The ships carpenter made a coffin of rough planks, and filled it with sand in the bottom. Then he bored holes in the side to make it sink faster. But it didn’t sink fast,

and as the wood in the coffin had a pale color we could watch it for a long time as it was slowly sinking."

“You must have been devastated.”

“Yes, of course, we were, and if it weren’t for the necessity of making sure that Knud didn’t catch it too, I don’t know how we could’ve kept going. I can hardly remember any of the details of the journey

after that. We arrived in New York, we got a steamboat to Albany and then went on the Great Lakes, much as my brother said in his letters, and finally on August 5th, we arrived in Moscow, Wisconsin.”

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Full of detail and historical

Full of detail and historical context -where do you find the time to research all this stuff? Incredible. Wasn't Abraham Lincoln an officer in the Black Hawk wars?

Thanks for reading. I am grateful for your time.

- Log in to post comments

Cholera on the ship, terrible

Cholera on the ship, terrible! We emigrated by ship, right across the world, and I still remember that first week of sea sickness, but of course conditions were good, I can imagine how horrendous this journey must have been. What a terrible massacre too.

- Log in to post comments

Amazing detail again. makes

Amazing detail again. makes it very vivid. And that a few years brought the change from sail only to steamboats. Rhiannon

- Log in to post comments

This is brilliant, Jean.

This is brilliant, Jean. Great to see how the relationship is gradually opening up.

- Log in to post comments