Marple and the Chartists 4

By jeand

- 1596 reads

Marple

August, 1842

The next day was Sunday, and the routine seemed much as always. I went to Sunday school, followed by church. I noticed that Mrs. Isherwood was in church, but didn’t make any move to speak to her. Afterwards I was waylaid by Beth.

“I wonder how Johnny is. Have you heard anything?”

“No, why should I? Do you think something is wrong?”

“No, not really, but he sent me a message yesterday, which I didn’t really understand. I hope he is all right.”

“You will no doubt hear from him soon,” I said and rushed off home to help with the dinner.

Later that day, Mamma called to me. “Eliza, you won’t believe it, but I think Mrs. Isherwood from the Hall would like you to go to work for her half days from September. Mrs. Fell apparently recommended you, when she said she wanted a young reliable girl from this parish to help her. I said I thought you would be willing. How do you feel about it?”

“Oh, I would love to do it. What sorts of things would I have to do?”

“Well you will have to wait for Mrs. Isherwood to tell you that. The idea is that if you agree, you are to go to the Hall next Saturday at nine, and she will explain your duties to you.”

“Will I be paid?”

“Yes, the wages are threpence for each morning’s work, to be increased after three months if you are found suitable. If your work continues to please, she will offer you permanent work at a much higher wage when you leave school.”

“How do you feel about it, Mamma?”

“I can’t believe that we could be so lucky. Up till now, she has hired no local girls as servants at the Hall. You must work hard for her and not let us down.”

“I promise Mamma. I will work hard. I do think she is a lovely lady when I see her at church with her baby. And she does a lot of good things for the town, too.”

“Yes, we are very lucky to have such a good provider in our gentry here.”

I was excited to share my good news with my schoolmates, but I found a mixture of surprise and jealousy amongst them, everyone wanting to know why I had been picked.

Later that week, on Beth’s half day off work, she came home as usual but she seemed very low. When she had a moment alone with me she explained.

“I heard from one of his friends that Johnny might be in trouble. He didn’t come home. He apparently set out to do some work in relation to his Chartist activities on Saturday, and as a result of some misunderstanding, he was taken in and I don’t even know where he is being held.” She was near to tears.

“Oh, no. How dreadful.”

Beth seemed surprised at the tone of my concern. “Do you know anything about this?” she asked sharply.

“No, of course not, but he is such a lovely man, your Johnny. I don’t want him to be in trouble. What will happen to him?”

“I really don’t know. His friend who told me about it said he would keep me informed, but I am so very worried about him. He only meant for good to come of his activities. He often told me that he had a mission to change the way our country worked. And now I don’t even know if he's all right,” and she started to cry in earnest. I comforted her as best I could, but I also decided that the first thing I would find out when I went to the Hall on Saturday was how this had come about.

On Saturday, before I started for Marple Hall, I called in briefly on my sister. “I will see if my friend Mrs. Isherwood can find out anything about Johnny for you,” I said.

“Why should she?”

“She has influential friends I would think.”

“How do you know so much about her? Have you already met her except for at church?”

“Well, not really, but we did have words on one occasion in the past.”

“Well if she can find out anything, which I doubt, I will be pleased. I am so worried about him.”

Nine sharp was the official time for my appointment. It took me 25 minutes to walk from our house to the Hall. It had taken less on the previous occasion but then I had been running. This time I was dressed in my best, and didn’t want to arrive sweaty and out of breath.

The Cook, who said she was called Mrs. Isabella Hood, ushered me in the back door, and said she would tell Mrs. Isherwood that I had arrived. I stood awkwardly and wondered how the other servants were going to take my arrival. The Cook, who looked about 30 to me, had a thick Yorkshire accent and hadn’t seemed all that friendly.

Mrs. Isherwood came to the kitchen to meet me, and smiling held out her hand. “Eliza, I am very pleased to see you are prompt. You, of course, have met, Mrs. Hood. She comes from Knaresborough and has been with me for many years. I will introduce you to the other servants later. First I would like you to come with me into the morning room and I will outline your duties and the terms of your employment for you.”

I was relieved at such a friendly welcome and followed Mrs. Isherwood to a room near the back of the house. She sat at the table and I stood awkwardly next to it.

“Mrs. Isherwood, I know it is very rude of me to ask you a favour before I have begun to work for you, but my sister is very worried about her gentleman friend, Johnny. You know who I mean. The one who was here the other night. He hasn’t been heard of since. Is it possible for you to ask someone and find out about where he might be?”

“Oh, Eliza, I don’t need to ask anyone. I know. The next day after the riot Constable Jenkins came to see me. He wanted the exact details of what had happened. I had to give him Johnny’s name.”

“But you promised me that you wouldn’t tell of my involvement.”

“I didn’t mention you by name; I only said a little girl.”

“But they left. They didn’t do any harm.”

“Well, they didn’t do any harm here, but later that night they went to Stockport and did enormous damage. Windows broken, intimidation of anyone who was around. They broke into the workhouse at Shaw Heath in Stockport. People were badly hurt. The group were all arrested, and I’m afraid your sister’s friend Johnny is now in jail in Stockport.”

“Oh, no! How can I tell her that? What will happen to him now?”

“Well, if his involvement wasn’t too serious, he probably will come before the magistrates and get off with a warning and a fine. If he was one of those who was known to do damage or harm anyone, then he probably will be sent to prison in Chester, to await trial at the Assizes there. But I did get the impression from the Constable that he was considered one of the leaders so that is not a good sign.”

“Can you find out which of those is going to happen?”

“I will try. After all, I do have an interest in the case. I will let you know what I discover when you come to start work the first Monday of September. Now for your duties. I think I will start you out with dusting and polishing silver. I presume you have experience of both of those jobs.”

“We don’t have any silver at home, but I have done lots of dusting. And I am sure I can learn how to do silver. All my teachers say I am quick at learning.”

“Well, I will introduce you to our parlour maid, also called Eliza. She’s Eliza Gerrard and has been with us for ten years, since she was little older than you. Today she can demonstrate how the silver should be done. And when you are dusting, you must be very careful. Many of the vases and such are priceless antiques, irreplaceable.” She rang a bell to call the maid.

“I will be very careful. And do I get paid each week or each month or at the end of the year?”

Mrs. Isherwood laughed at my gaucheness. “The usual is an annual salary, with the first few months paid in advance so that the employee has some pocket money for expenses. We will provide you with a uniform. You are very small, but I think perhaps not much smaller than our kitchen maid. Can you sew?”

“Oh yes.”

“Well, you can wear one of hers for today, and then take it home, wash it, and make it fit you for when you start. I will make sure there are more ready for you in your actual size, by the first week of September.”

“Ah, here is Eliza. Eliza this is another Eliza who will be working here mornings from September until she finishes school and then will come on to the staff full time. You will need to train her in our ways of dusting and polishing silverware. She has no experience with silver whatsoever.”

“Yes, Ma’am. I will do that.”

“And stop in the laundry room and pick up one of Ann Metcalfe’s uniforms. Eliza can wear it today no matter how odd she looks in it, and then we will do better for her by the time she starts.”

“Yes, Ma’am.”

So that is how the day progressed. I looked very lost in the uniform, but not letting it get me down, I tightened the belt and rolled up the sleeves. I thought that Eliza was somewhat friendlier than the Cook had been, which I was relieved about. “How are we going to go on with us both with the same name?” she asked laughing. “I will be Old Eliza as I am 21 and you can be Young Eliza. How old are you anyway?”

“I’m nearly twelve.”

“I'm surprised that Mrs. Isherwood has taken on someone else. Have you some reason for being considered special? I noticed that she treated you very tenderly as if you were a relative or something?”

“No, of course not. We just have something in common.”

“And might I ask what that is?”

“I’m afraid I can’t tell you.”

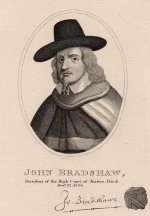

As we were going into the Judge’s bedroom, where we would start with the dusting she said, “I will tell you all about the ghosts, if you want to know. This is the bedroom used by Judge John Bradshawe, who signed the death certificate for King Charles I.”

“Are there lots of real ghosts, then?”

“Well, I am not sure that you can call ghosts real, but lots of people have seen them. I think I have seen the crying lady ghost, but since we are working in here, I will tell you about this room’s ghost, none other than Charles I. His headless body is seen stomping down the corridors on dark and gloomy nights.”

“Look here at this poem John Bradshawe (pictured above) scratched on the window. It says

My brother Henry shall heir the land

My brother Frank shall be at his command

While I poor Jack shall do that

Which the world will wonder at.

“Henry was his oldest brother, and he was a commander in the army that Cromwell set up. But John, who calls himself Jack, was the one who signed the death certificate for the King. Certainly that was something the world wondered at.”

“Was Charles I really so awful that he had to be killed?”

“Well, John must have thought so. Charles’ father, who was James I of England, he called Stinking Jimmy or something like that, but in quite an affectionate way. James’ eldest son, whom John thought would have made a good King when his turn came, died early. So Charles, who was a pleasure seeker and had not a whit of good sense about him, became King in his stead. He apparently didn’t pay any attention to Parliament, spent all the tax money on himself and the country was left to ruin.”

“I thought Cromwell was at the back of it all. That’s what we learned at school.”

“Well, of course Cromwell was important. He was the one who started off the whole idea of putting the King on trial. But when the King was found guilty, he wasn’t the first to sign the death warrant. His signature comes 3rdor 4thon the list.”

“Why couldn’t they have just exiled him or something rather than do that awful thing of beheading him?”

“Watch where you are dusting there. Those things are very valuable.”

“Sorry. I guess I was listening to your story rather than paying attention to what I was doing.”

“Well, the answer to your question is that John Bradshawe (he spelled the name with an extra e but most since him have spelled it without) didn’t trust that he could be contained. He thought that he would go off in exile to Europe and then persuade the other European heads of State to support him and start another war to get his kingdom back.”

“Well there was a war anyway, wasn’t there? The Civil War.”

“It was Charles I who started the Civil War and there were actually two of them. He proclaimed war on the Parliament. It went against the Magna Carta and all that this country was supposed to stand for.”

“So there were lots of battles, and in the end, it was the Parliament supporters who won. Why were they also called the Roundheads?”

“Well they were mainly Puritans, and they dressed very plainly and without embellishment. The men shaved a bald patch on their heads, I think. Although, John Bradshawe, for instance, did not lead the life of a proper Puritan. He enjoyed the pleasures of life as well as anybody.”

(to be continued)

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Seems a happy place to be

Seems a happy place to be employed, and snippets about history as you work! Rhiannon

- Log in to post comments

She's learning as much as she

She's learning as much as she might at school here. Young to work but an interesting place.

- Log in to post comments