Saint or Scoundrel 7

By jeand

- 1975 reads

April 9, 1863

I know that the news my father conveyed to Mr. Wakefield through his next letter was not pleasant to hear. Ellen Legh had a child in November, 1828, a son, but he was stillborn. How sad for her and her husband, and I also think that Edward, still having a great interest in her, would have been very upset on her behalf. He gave such a great importance to his own children.

I confided in my employer, Mr. Balshaw, about my frustration over not knowing how to end my book, once the letters run out. He suggested that I look out the death notice in the papers and find out if Mr. Wakefield had any relatives still living in this country. I feel much relieved at what was an obvious solution to my problem, and yet I couldn’t see it myself. I will do that soon.

November 25, 1828

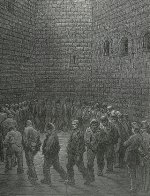

Newgate Prison

My dear Daniel,

I didn’t know. I hadn’t heard. I feel wretched for poor Ellen. How

she must be suffering. If only I could do something to ease her pain.

Would you do something for me? Would you take a posy to the grave - I

expect not much is blooming this time of the year, but even if it is

holly berries, make it into a nice bunch and put it on the grave for me. I

can’t put my name to it, but I feel the need of making some sort of

gesture.

I got the impression from your last letter that I haven’t done a good

job in explaining just how dreadful this place is for most of the

inmates. My case is certainly not typical.

Of the 150 prisons in London, Newgate is the largest, most notorious and

the worst. It has room for between 40 and 50 prisoners. Because

prisons are privately run, any time spent in prison has to be paid

for by the prisoner and being a gaoler is a lucrative position.

‘Garnish’ is the fee paid on arrival, payments for candles, soap

and other supplies also have to be made. Heavy manacles - often

painfully constricting - are often attached to prisoners and then

secured to chains and staples in the floor. The prisoner can pay to

have lighter manacles fitted, ‘easement of irons’, or have them

removed entirely. The freedom to walk around can also be bought, if

enough money changes hands. Prisoners are also housed according to

their ability to pay, ranging from a private cell with a cleaning

woman (like I have) and a visiting prostitute (which I don’t have),

to simply lying on the floor with no cover and barely any clothes.

Lice are everywhere, and only a quarter of the prisoners survive

until their execution day. Infectious diseases like typhus, the

so-called ‘gaol-fever’, which are spread throughout the prison by

lice and fleas, kill far more people than the gallows.

Food is provided by the authorities, and by charities to those who can not

pay, but cooking isn't included and so it is often eaten raw.

Drink is also available - the prison has a bar - although the prices are

extortionate. Leaving prison is not simply a matter of finishing a

sentence and walking out. A departure fee has to be paid and, until

it is, prisoners can not leave.

Those who die inside have to stay here as a rotting corpse until relatives

find the money for the body to be released. The stench is

unimaginable, and unavoidable for all of us. Nearby shops are often

forced to close in the summer because of the unbearable smell. It

isn't unusual for children to be conceived and born inside the

prison, for men and women freely mingle, and the women find that they

can swap their favours for food; and if they become pregnant they can

‘plead the belly’ in an attempt to avoid hanging. Surviving

children are taken to the workhouse, where their chances aren't much

better.

Well, now you know why I feel it imperative to do all I can to help my

fellow inmates.

Hoping that this finds you well, I am

Your friend,

Edward Gibbon

May 12, 1863

I have had the most extraordinary letter. I really do not know what to make of it. It came in the post today, a fancy thick embossed envelope with the Shrigley Hall coat of arms on it.

May 11, 1863

Shrigley Hall,

Pott Shrigley,

Cheshire

Miss Margaret Forbes

7 George Street

Altrincham, Cheshire

Dear Miss Forbes,

In a recent discussion with my housekeeper, Mrs. Herman, she mentioned that she had heard via the postmaster at Poynton-Worth that someone was writing a book about my deceased mother. After much prodding, your name was produced, and she admitted giving you the name of an

elderly publican as a source of information for your book.

Surely, Miss Forbes, the correct procedure would have been for you to contact me directly, rather than depend on tittle tattle from servants and peasants. If you in truth are writing a book about my mother, I would be the one with the most reliable information. I can only assume that

you were too humble to approach me directly.

Therefore, I am going to take the matter in my own hands, and invite you here for tea on Sunday, the 24th at about 3 p.m. I would expect you can get a train from Altrincham to Poynton, and if we know the time of your arrival, we can see that there is a carriage to meet you and bring you here. We would, of course, take you to the station for your return journey.

Please bring with you any information that you have already gleaned about my mother, so I can ascertain as to whether it is accurate. I only hope that you are not intending to stir up yet again the story of her abduction, as she, surely, after all this time, should be allowed to rest in peace. My father, who was her husband, died eight years ago.

Please inform me of your intentions in this regard.

Yours faithfully,

Ellen Jane Legh Lowther

I showed the letter to Mr. Balshaw and he agreed that it would be useful for me to have this contact. I might find out more about her mother, which could only add to my book. And he says I need not be

intimidated by her manner. Her mother’s life is a matter of public record, and there is no reason why one cannot write about it without the daughter’s permission. However, he suggests that I downplay the real objective of my book, in order not to antagonise her. And so in less than a fortnight, I will be able, hopefully, to make my book more accurate and meaningful.

Here is Edward’s next letter to my Pa.

December 10th, 1829

My dear Daniel,

You will be interested to know that my ideas about colonization are

causing quite a stir. As I told you before, I wrote a series of

letters about systematic colonization which was published in the

London Morning Chronicle. The letters aroused such interest they were

republished in book form edited by Robert Gouger.

In the letters I pretend that I am a surgeon gone out to Australia in an

emigrant vessel.

Here is an extract from it. (I am talking about the useage of women who

arrive in Australia.)

“The emigrants whom we took out as well as those in two other ships, which

have arrived since, were immediately on their arrival engaged;

housemaids at about £17 and cooks about £20 a year. Married people

get from £25 to £40 a year, with rations and a log cabin to live

in. It does seem that in an emergency of this kind, nature with a

voice more potent than that of political economy, dictates the course

we should pursue. If as appears to be the case, we have broken the

order which is said to be the first law of Heaven, our punishment

great as it is, does not exceed our fault.

“We have sent to Australia the strong hands which should have been the

protection and support of the starving needle-women; and we have

denied the emigrant on a foreign soil his natural helpmate, with no

other result but that of creating a plague-spot in the centre of

society at home. This emigration movement is one on which we have

greatly prided ourselves, and by which we have all to some extent

profited; it has been extensively promoted by the state, and

stimulated by private enterprise.

“If then, it has been so imperfectly and partially worked out, the extent

of our previous negligence should be considered as the measure of our

responsibility to repair the evil. Mr. Herbert’s plan of a society

to promote the emigration of respectable females to Australia is an

attempt to pay this debt, and hence its claim on public support. It

has a just demand on private benevolence, and on the state

conscience. It is one of those few schemes of wholesale alms-giving

which are unattended with any danger, and which, while they give

great temporary relief, may be also expected to produce a certain

degree of more permanent good.”

I won’t go on with it, but perhaps you can get a flavour of what I am

trying to convey. I wish you and your family the best Christmas.

Hopefully, it will be the last I spend in captivity.

Yours,

Edward Gibbon

- Log in to post comments

Comments

The conditions in the prison

The conditions in the prison certainly were dismal. Again, how lucky were the ones who could pay.

Looking forward to the next.

- Log in to post comments

Grim indeed, jean, the scene

Grim indeed, jean, the scene you paint inside the prison. Look forward, like Bee, to some more.

Tina

- Log in to post comments

'The prison has a bar

'The prison has a bar although prices are extortionate' And iron bars on the outside too. What more does the man want?

Joking apart, you have done your research very thoroughly and it is certainly informative reading Elsie

- Log in to post comments

Lots of really interesting

Lots of really interesting information here Jean, and very well told.

Lindy

- Log in to post comments