You and I are Earth

By Tommy Dakar

- 1494 reads

YOU AND I ARE EARTH

The battered white van crept unnoticed into the dimly lit service alley and parked up against a high brick wall. Unnoticed, because all attention was centred on the town square, where in a few minutes’ time a firework display would mark the end of the local fair. Two men climbed out of the van and hauled themselves up to the roof. They unhooked an aluminium ladder and a hold-all from the roof rack, working steadily, silently, with the co-ordinated movements of professionals. The ladder, padded in parts with sackcloth and secured to the top of the van by nylon ropes, was thrown over the brick wall. Carefully, avoiding the shards of broken glass that topped the wall, the two men climbed down into the back yard of the establishment, one of them with the hold-all on his back like a rucksack, his arms thrust through the handles. They waited.

The revellers filled the square, which was formed by the imposing façades of the Town Hall, All Saints Church, a Bank, and the Police Station. A large coffee bar on one corner supplied modern day bread and circus. They were all facing a temporary stage placed before the main doors of the Town Hall. Tonight, after the fireworks, there would be music.

As the clocks struck eleven, up went the first rockets, and down came the men’s sledgehammers, smashing into angel’s heads, into the swollen bellies of Phoenician urns, into daintily decorated porcelain garden lamps. In syncopated rhythm the rockets burst, showering the onlookers with myriad coloured sparks, as the gaily painted ceramics exploded into thousands of fragments, their varnished colours quickly dying in the darkness of the yard.

The fireworks ended sooner than the men had suspected - a question of municipal economics. But they had not finished yet. They waited for the band to strike up. With the first chords they would break into the main building itself, through the double metal doors, and devastate the exhibition room where the really valuable stuff was housed. Breathing heavily they leant on their hammers among the shattered earthenware for the music to start. An ear-piercing feedback stabbed the silence, followed by a large groan from the crowd. Technical problems. Three minutes later they were forced to admit defeat, there would be no more music tonight. They scrambled back up the ladder, stored their tools, and crept back out into the lights of the town.

The old town of Stilbury had been surrounded by a necklace of ring roads and roundabouts, like a tarmac- grey string of pearls. Whether the intention of the urban planners had been to adorn or strangle the city was a matter of debate. Along these bleak dual carriageways a host of functional warehouses and services stations had sprung up like trees along a river bank. Trees sought water and trace elements; discount stores and leisure centres came in search of access routes and parking space. It was their natural habitat.

Stilbury was dwindling, its population trickling away to larger cities. Despite the industrial estates, despite the Congress Centre, despite the demolition of every building over fifty years old. Once famous, at least locally, for its ceramic trade, the town had fallen prey to World Economics. Somewhere a handful of people were playing real Monopoly, gobbling up properties and amenities and laughing all the way past Go, whilst others went bankrupt. Rules of the game. Not so long ago there had been over a hundred working kilns in Stilbury, producing some of the finest pottery in the area. Today all but one had been bulldozed for redevelopment.

The new Stilbury was a drab affair. Only a few streets remained of the historical centre, marred with office blocks and plate glass shop fronts which had somehow managed to squeeze themselves between the traditional buildings despite the uproar. Anonymous architecture, cloned from a thousand other towns worldwide, offered a dull backdrop to the listless townsfolk. It was ironic that Stilbury, in the past a town renowned for its things of beauty, should now be reduced to this insipid, uninspiring present, as if the aesthetic and the functional were mutually exclusive.

But the terrible truth was that nobody bought ceramics anymore. They were expensive and impractical. Plastic substitutes could be found for a fraction of the cost. Or cheap imported versions. Why pay more? Bailey’s had at last gone under, the largest manufacturer the town had ever known, and one of the oldest too. Sold out to a DIY franchise.

Coming into town off the M17, exit 43, the foundations of the long heralded Pottery Museum could be seen like archaeological remains, abandoned to the approach of weeds and vermin. It would never be finished now, arts funding being a thing of the past. The treasures intended to find their eternal rest in Stilbury Pottery Museum could now be seen in a modest exhibition at the back of My Old China Shop, just off the town square.

Ted Turnbull, the proprietor and master craftsman of the shop, and of the last working kiln in Stilbury, was under as much pressure as the town itself. One by one he had seen how his fellow potters had been forced to close, unable to weather the storm, unable to survive without protection in the Free Trade Zone. Market forces the media said. Law of the jungle it used to be called. But Ted Turnbull struggled on, against the odds, against his family’s advice, against financial logic, like Canute fighting back the waves of change; stubborn, resolute, and doomed to eventual failure.

The other kilns had moved on; he would stay. The local council had refused to fund the Pottery Museum; he would house it. Other shops had given in to the persuasive tactics and ready cash of the import trade; he would hang on. He would not sell trash, he would not abandon the skills he had perfected over a lifetime, he would not sell out to the highest bidder. Ted Turnbull would continue to create things of beauty, even if no-one wanted them, even if he never sold another one in his life, even if all they would do was gather dust in his makeshift exhibition room.

Because he had to admit business was slack. Even his less artistic work was of the highest quality, but with a price tag that reflected the hours spent in its manufacture. His earthenware urns, his decorative figures, even his lowly plant pots, were considered luxury items by most of the townsfolk and sold slowly. So when he arrived on Monday morning to find that almost every single piece stored in the backyard had been destroyed, deliberately vandalised by persons unknown, though heavily suspected, he realised that final defeat was not far away. Luckily they had not ventured into the exhibition area, and his most prized items remained intact. For now.

When it came to business affairs there were many adjectives that could be used to describe Xiong Liu – ruthless, unscrupulous, heartless, ambitious, persistent, aggressive. He had accepted as a young man that all these traits would be necessary if he were to succeed in the cut throat world of international commerce. They were values to be encouraged, nurtured, values to be proud of. Now that he was influential, now that he had managed to pull his family out of rural poverty, now that he was powerful and rich, he had no intention of changing tactics.

He stood at the door to one of his local emporiums, dressed in a flashy dark suit, with a green silk shirt and a bright yellow tie, with mirrored sunglasses on his head like a silver hairband. When he saw the two men arrive he motioned that they follow him through the store to his office cum warehouse at the back of the premises. As he walked proudly along the aisles of bright plastic junk, pointing at this and that, he resembled the early white traders in Africa, selling baubles to the ignorant and fascinated natives in return for their most valuable goods.

The men had come for their money. But they had not completed the job. They tried to explain. Excuses. They would receive payment, as always, on completion of the assigned task. That was final.

Xiong Liu’s face was expressionless, unfathomable. By choice he was a man of few words, as his profession demanded. But what he was thinking was that he wanted those premises, it was a prime spot, and the old man was wasting everybody’s time. He was a fool, a failure. Worse, he was a romantic. He made things of the past, things nobody was interested in anymore. Let him roll over and die.

On completion. But wait for instructions. Go now.

Ted Turnbull went to the police who were sympathetic. They would do what they could, which meant a visit, some photos, some paperwork. Broken pottery was not high on their list of priorities, and although Ted had his suspicions, they were no more than that. Until hard evidence was found it was best to let the insurance company take over, which meant a visit, some photos, some paperwork. And a serious doubt about the ‘acts of vandalism’ opt out clause. So Ted cleaned up the mess and went back to work. He needed more clay, but his usual contact was unable to supply him any longer, claiming that it was more trouble than it was worth. He cast around for another source, but as only the best would do for Ted Turnbull, he had to look farther afield to find what he wanted, and the transport costs would mean upping his prices once more. There was nothing he could do; he would have to abandon all but the highest quality ceramics, and see how long he could resist. He could feel the rope tighten around his neck.

Xiong Liu was waiting for My Old China Shop to fall like a ripened plum. He had chased off Ted’s supplier, he had spoken to the transport companies, and he had stuffed his own shop windows full of cheap ceramics, from plant pots to hand painted figures. Very soon now that property would be his. There was no remorse, no sympathy, no sentimentality. Xiong Liu had won; it was as simple as that. Mr. Turnbull had had his day, now he was finished, obsolete. The things he had created and was so proud of meant nothing to anyone anymore, were only museum pieces, extremely fragile, and once broken only fit for the bin.

He knew he would not need to send the men back to finish their business. It was just a question of time. Time for Ted Turnbull to beseech the local council once more about the never-to-be museum, time for his remaining stock to run out, time for the overheads to weigh him down. Time for Mr. Turnbull to accept, if not defeat, at least early retirement.

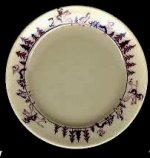

A few months later Xiong Liu, accompanied by his sister and his brother-in-law, entered the empty premises. There was dust everywhere, and scraps of cardboard littered the floor. They would strip it all down, throw out the old counter and shelves, change the lighting, give it a lick of paint, and stack it full of the imported knick knacks that sold so well. He picked his way towards the old office, trying not to soil his shiny new boots. On Ted Turnbull’s desk was a parcel, perfectly wrapped in brown paper and tied with string. It read: For the new owner. Xiong Liu examined it carefully, almost as if it were a booby trap. What was this? A present? A joke? Some kind of revenge? He showed it to his family, who urged him to open it. Very slowly he untied the string and folded back the wrapping. Inside was a hand written note, a small white dish no larger than a saucer, and a plasticized card. Baffled, he handed the note and card to his sister who read English a lot better than he did.

The note read: Please accept this small gift. It is, in my opinion, the most valuable object in the collection.

The card read: This small, white, bone china dish was found in a London sewer in 1973. It was made in Stilbury by Baliley’s and Sons aprrox. 1810-1820. How it came to end up in a sewer, and how it managed to survive unscathed for so long is a mystery. Still legible around the rim is the legend - You and I are Earth.

Xiong Liu picked up the dish and examined it. You and I are Earth. Then he flung back his head and laughed until tears came to his eyes.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

brilliant. You and I are

brilliant. You and I are earth indeed.

- Log in to post comments