widdershins

By celticman

- 4389 reads

You probably remember that story of the Virgin Mary turning up unexpectedly at her pal’s house, as she’s prone to do, and blurting out: ‘hi, you’re pregnant’.

And the auld dear saying, ‘that’ll be chocolate, I’m nearly thirty, well past it, we’ve been trying since I got married at nine, but you know what God’s like. Not that I’m blaming HIM. He’s got enough to worry about with all these Romans running about, no even believing in HIM and mocking the Sabbath by getting drunk and spitting in the Cornflakes other folk need to eat’.

That’s like getting caught het. I was one of those celebratory babies and we weren’t even Jews. Mum was nearly 40 and dad was nearer to kicking the bucket than that. He’d been born before or after the Great War to end all Wars. He spoke in grunts, and if every grunt was a ring in a tree, he was older than Sherwood. Nothing was ever right with him unless it was wrong. The Great Depression was a natural expression of his temperament. He left school at twelve, because that’s what you did, and was a docker on the Clyde and worked alongside other dockers that didn’t have any work. He was small for his age and kinda humpbacked, but he made up for it by pushing out his pigeon chest when they met at the docks at dawn, and waited, while bowler-hatted bosses slipped workers a token marker that entitled them to a day’s wage, after doing two-day’s work emptying the holds of ships. The only time he was picked was when his piece, a bit of bread and scraping, was taken from his pocket. Dad just loved the Second World War because not only did it save the world from Fascism, it meant that he could slip lots of cans of stuff, like tinned fruits, which were the Del Monte nectar of the Olympian heathen gods, into the poacher pockets, and he came home rattling.

Mum was Mum, leftover scrapings from the charity shop, a wee orphan woman with a body like a cut-glass bowl for carrying things. When people referred to her, which didn’t happen very often, they would say something like she’d a remarkable pair of lungs, which told you exactly what she looked like and what they thought of her. She didn’t wash very much either, but that wasn’t her fault that was the asthma.

I didn’t know I was a snotty and smelly wee child. I’d all the right parts, all five fingers and five toes and all that malarkey, but they wanted the baby Jesus that would just lie swaddled in his cot and shut up, until HE was about thirty-two in the Roman calendar, then go quietly about HIS FATHER’S business, without any much bother. He might have got lost once or twice and he did get crucified, which might have been a pain in the arse for some parent, but let’s face it, we’ll all got our crosses to bear. They christened me John.

Christmas was a tradition we often missed. Mum stocked up not on stockings, but tins in the back cupboard in the kitchen, brought forth to multiply when opened. A nuclear war for me brought the hope of an end to bully beef. Mum cooked with a tin opener and wore a threaded nylon apron most of her life. Our one pot’s handle was broken Bakelite and anything heated was a confused mess without the blender. Anything not fresh was cooked until it hurt and then cooked until properly black. Anything uncooked was fresh. Milk left lying on the windowsill curdled in the heat, flies taking their picking, but tripe was cheap meat and soaked in milk was an economy that could not be sniffed at. We had the last laugh, because the remains went in the sponge mix and beaten with an egg. No one at Christmas went without pudding. God be praised.

Usually its’s raining, but if God did make sunshine, and made everything why didn’t HE make a fridge for us? That was the kind of question I wanted to ask HIM. Everybody else had one, and they didn’t need to wear hand me downs from my Dad and Mum to school. I didn’t have the savvy in Primary Two in St Stephen’s school to say, ‘hey, I’m Scottish, that’s no a skirty, it’s a kilt, without the tartan’. Other kids thought I was weird. I thought I was weird too. We could have a lot in common and discussed it. But in those days everybody just battered you for being cheeky, or for looking at them the wrang way, or just looking like you might look at them the wrang way. Counselling meant, ‘shut up and get on with it, or I’ll need to batter you as well, but for your own good’. The weirdest thing of all was I quite liked school. Free-School dinners were gourmet cooking. Miss Monaghan was cute and she smelled nice and didn’t shout very much. Sometimes she smiled in my general direction. I’d smile back, but she’d look away and correct something or somebody else. I didn’t blame her. Sweets and spice and all things nice, just wasnae me. Everything was a conscious effort and I was looking into other people’s life from the outside.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

I liked this.

I liked this.

So you're weird, right? Weird makes a good writer in my humble opinion.

- Log in to post comments

A lovely reflective piece of

A lovely reflective piece of another world we seem to be hurtling back to (ten years ago I'd have written 'hopefully left behind' - wish I could say the same now).

- Log in to post comments

This is our Facebook and

This is our Facebook and Twitter Pick of the Day!

Please share/retweet if you like it

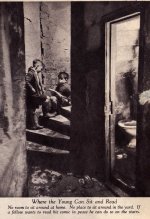

Picture Credit: http://tinyurl.com/zt97weq(link is external)

- Log in to post comments

love that nuclear war line

love that nuclear war line

- Log in to post comments

Natural born writer. The

Natural born writer. The child's tender understanding is so touching.

- Log in to post comments

full of verve

Completely bounces along in very good way, great descriptions of character, senses and sights. I love Miss Monoghan, I so hope she helps him. Well done. Would your mum be cut glass bowl or something tougher?

- Log in to post comments