Dogsbody (3)

By HarryC

- 551 reads

After the pub job, my money soon dried up. I was back to making calls and going through the local papers.

One evening, Mr Watson – a tall elderly man with a crooked nose and huge bushy eyebrows - came and knocked at our door. He was the warden of the local church. Dad called him 'Sir' and offered him a glass of cider from our weekly barrel, which he politely refused. He said he knew I was looking for work and asked if I'd like to cut the grass in the church yard.

"The pay is £8 a cut," he said.

I agreed, thinking it would be a morning’s work – a day at most.

I met him up at the church the next day. It was the first time I’d been in the church yard. Calling it a yard was like calling Buckingham Palace a house. It looked like Putney Common, where I’d played as a kid. From the gate, where we stood, I couldn't see the boundary in any direction.

"We haven't managed to get anyone to do the job for a while," Mr Watson said, as we waded through the undergrowth to the tool store.

That, too, was an underestimate. It had to be years. Decades more likely. The grass was so long that the gravestones looked like the tiny humps of whales swimming through a vast, wind-swept ocean.

Inside the store were a hand scythe, a sickle, a grass rake and an old ‘push’ mower, with a blade head about the width of a doormat. In one corner, among a pile of rags and old newspapers, was an oil can, a whet stone and a pair of grass shears with rusty blades and worm-holed wooden handles.

“It might all need a bit of a sharpening up,” said Mr Watson. There was a tone in his voice as he said it. I didn’t know if he was trying to be funny, or if he was just unaccountably optimistic about it all. The place needed a combine harvester at least. This would be like trying to shear a herd of sheep with a pair of nail scissors.

“Start when you want to,” he said, cheerfully. “Soon as you can, though, really, as they’re forecasting rain next week.”

He gave me the key to the store.

“Just drop it back through my letterbox when you’ve finished with it of a day. See how you get on. Good luck. You’ll get paid when it’s all done.”

I started at nine the next morning. By lunchtime, I’d barely cut the size of a small garden. The mower blades were blunt. The shear blades tended to fold the grass stems over rather than cut them. I tried the sickle, but the blade kept falling out of the handle. The scythe just pushed everything over. By the end of the day, I'd hardly cut enough grass for a couple of hay bales. Mr Watson came up and looked at what I’d done. I felt like I was having my school work judged by a strict teacher.

“Oh well,” he sighed. “Just crack on as best you can.”

I worked alone every day. By the end of the week, I’d barely managed a quarter of the entire churchyard, and the area I had cut was already beginning to grow again. Mr Watson surveyed it all and rubbed his chin.

“Maybe it’s a bigger job than I thought. I’ll see if I can get you some help. We’ve got a wedding here next Saturday and we really need to have it done by then.”

By the middle of the following week, I’d begun to see more and more people working on the job – retired people from the village, then others coming along after work in the evenings, all of them bringing their own mowers and shears and bottles of water or cider. It became a community event, with bods everywhere hacking and shearing and mowing. We finally managed to get it all done by sundown on the Friday.

The next morning, Mr Watson called down and gave me an envelope with four pounds in it.

“I thought you said it was eight pounds for the cut," I said.

He shook his head, as if I'd uttered a profanity.

“You didn’t do the whole job, did you. It’s only fair.”

“But he was up there every day,” said dad.

“I’m sorry, but it’s all we can manage.”

After he’d gone, dad was furious.

“That's the bloody church all over! Never give you nothing. Then nail you up in a wooden box and stick a bloody stone on yer 'ead when yer dead. Wouldn’t give a dying man a soddin' toothache.”

I kept trying with the phone calls and papers, but didn't see anything I had the experience for, or that would take someone without qualifications. Even some of the shop jobs I saw advertised wanted O levels. A few of our neighbours around knew that I was looking for work, too. Mum and dad had got friendly with a couple who lived just down the hill from us. Barbara and Les were the same age as mum and dad. They were native Devonians and had lived in the village their entire lives. They had a son, Ken, who worked on one of the local papers. I played snooker with him sometimes at the club. He had a unique approach to the game. He had a good eye for a pot, but he played every shot like he was firing a rifle at a fast-moving animal - WHAM! SMASH! - sending the balls scattering like atoms in the hope that something would drop in somewhere - as one or two usually did.

One day, after work, he called over with a copy of the latest Newton Abbot Times.

"Hot off the press," he said. "There's one there might be worth a go."

I had a look at the ad he'd circled.

ASSISTANT CELLARMAN

REQUIRED

DALE'S DEVON CIDER

PENSCOVE

40 hours per week

Good rate of pay

Apply in writing

Dale's was the scrumpy they served up at the club and in the pub. Dad always drank it now, saying it was the best cider he'd ever drunk.

"I know the place," Ken said. "It's out other side of Totnes. Little village up off the Buckfastleigh road."

"That'll be handy if you can get that," dad said. "You might get staff discount."

"I guessed that's what you'd be thinking," said mum.

"Thanks, Ken," I said.

"That's alright. You've seen it afore anyone else. Get in first."

"I will," I said.

"Okay. Might see you for a game later."

I sat down at the table and wrote the letter as carefully as I could, though my handwriting was always shocking. It was something I'd never learned to do properly. My words were full of eccentric loops and tottering uprights, and my lines always tended to curve downhill towards the end. It was one of the many things that got me singled out as thick at school. I ended up writing it several times before I had it as I wanted it - just saying how old I was, that I'd just left school, that I was fit and strong, etc. I mentioned my work at the garage, and the other odd jobs I'd done. I wanted to make them think I wasn't afraid of work. When I was finally satisfied with the letter, I went out and posted it off, including a self-addressed envelope for reply. Mum said that would go down well. A couple of days later I got a letter back inviting me for an interview on the following Monday.

This was my first ever proper job interview and mum insisted that I put a shirt and tie on. I hated wearing ties as they reminded me too much of school. But I put one on to please her - with a zip-up jersey to cover it. I wore my only pair of smart trousers and some black shoes that dad had spit-and-polished up for me.

Getting to the interview was the next challenge. I got the Old Forge taxi to Totnes, then got the Ashburton bus which travelled through all the villages. It took over an hour before the driver finally put me down at the village crossroads. I saw a woman hanging out some washing in her garden and asked her where the cider works was. She told me her husband worked there, too.

"Down this lane and around the bend, then down the hill to the junction. You'll see the big manor house in front of you. That's where you want."

As I walked down the lane, I came to a gap in the hedge on my right - and through it I could see the knuckle-end of Hay Tor out on the moor. It didn't look very far away. Maybe a few miles. It felt like a good omen, seeing it there like that - and being so close to my favourite place in the world. Dartmoor.

The manor house was huge - one of the biggest houses I'd ever seen, standing alone like that behind high granite walls. From the steps outside the studded front door, two stone lions crouched, glaring at me. Somebody rich lived in there, that was obvious. To the right of it, beyond the boundary wall, a short driveway led into a yard, where I could see some old stone farm buildings, and a tractor parked up. The place seemed deserted, though. I walked into the yard and looked around. There was a weighbridge on one side, with a little wooden shed. I headed over to the buildings and saw a gate leading into a large enclosure. I could hear animal sounds and the noise of a milking machine, but still there was no sign of anyone. Beside the weighbridge, some steps led down to the back of the house. As I looked, a man came up them. He was about thirty, dressed in green dungarees, a trilby hat and green wellingtons. And he was tall. I was already over six feet, but I had to look up to him. He wasn't just tall, either. He was wide. His shoulders were as broad as a car axle. He looked at me quizzically.

"Are you Will?"

"Yes."

He extended a hand the size of a shovel.

"I'm Richard Dale. You're here about the job."

"Yes."

He didn't look rich to me. But then I'd never met a rich person before. It was Devon, so I guessed they wouldn't look like normal rich people, anyway.

He turned back towards the steps.

"Follow me."

We descended to a small courtyard at one corner of the house. I could see the garden stretching off at the back. It looked like an entire allotment. We went in through a side door and along an echoey stone hallway, then turned off into a small room where there was a table and a couple of chairs by a back window. It was obviously a store room. There were a couple of big chest freezers, crates of dog food, shelves of tins and packets. I couldn't believe anyone could have a room as big as this just for stuff we kept in a cupboard at home. I couldn't believe anyone could have a house this big. I thought it probably had its own snooker room somewhere.

It wasn't much of an interview, really. He asked me about the jobs I'd mentioned. He asked me about school. Thankfully, he didn't ask me what qualifications I'd got. Then he asked about hobbies. I said I did karate. It wasn't really a lie. I had a book on karate at home and had been trying to learn some of the moves. But I didn't really know anything about it.

"Well, I can see you're strapping enough, anyway," he said.

It could only have been because I had that thick jersey on. Then he told me about the job. He said I'd be working with the head cellarman, and replacing another chap who was retiring. Mainly, it was washing out the cider barrels and jars, filling them up for delivery, sometimes helping out with the deliveries. He said the place was also a working dairy and pig farm, and sometimes I might be called on to help with moving animals or something like that. And haymaking in the summer, of course.

"You'll also be helping to make the cider," he said. "We start pounding the apples at the end of October. It lasts about a month. It's going all day, non-stop, from seven-thirty in the morning when you start until eight-thirty at night. So there's overtime then. Your normal hours are seven-thirty until five, with half-hour for breakfast and an hour for lunch. So, it's forty hours a week, sixty pence an hour. How does that sound?"

I tried to work it out. Twenty something.

"Twenty four pounds a week," he went on. "Paid in cash on Friday. No weekends. Sound alright?"

"Yes," I said. It sounded great.

"What about getting here?" he asked. "You got a bike or something?"

"No. I'll see if I can get a moped."

He nodded. "If you need an advance to put a deposit down, I can take it from your wages."

"Thank you," I said. I didn't know what else to say.

"Okay." He put his hand out across the table and I shook it again. "We'll look to start you in a couple of weeks if we can. Give you chance to sort things out."

And that was it. I had a job. My first real job. And I was going to buy a moped. It felt like the world was opening up and starting to come right at last. It was all happening.

"I'll put you a letter in the post later, confirming," he said.

He walked me back up the steps and said cheerio. Then he went off through the gate into the yard.

I made my way back up to the bus stop at the crossroads - my head spinning with visions of money, mopeds, LPs, cigars.

I was the happiest man alive.

Well... almost man.

(continued)

- Log in to post comments

Comments

More than I earned in my

More than I earned in my first job!

- Log in to post comments

Hi Harry,

Hi Harry,

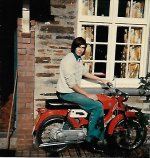

was that your first bike in the photo above? I took motorbike lessons when I was seventeen, but failed the test and never took it again. Got a Hillman Imp instead and passed my driving test first time thankfully, much to the relief of my mum, she never did take to motorbikes, said they were dangerous, but I loved riding on the back of them, had many happy memories of boyfriends tearing up roads...happy days.

I bet you were really chuffed to have got your very first full time job. Good on you for persevering. I look forward to finding out how things go.

Jenny.

- Log in to post comments

That sounds a wide variety of

That sounds a wide variety of duties! Was it good, to be at the beginning of the cider being made, all the way through to delivering it? Then going home and your Dad has it after his work :0) Must have smelled amazing, crushing apples. Another brilliantly involving story!

- Log in to post comments

I remember my eldest son

I remember my eldest son getting a Saturday job, or holiday job, on an apple farm, and learning to drive (on a tractor) there and I think getting involved in the pulping. He was so glad to get the job and really enjoyed it. Rhiannon

- Log in to post comments