Tormore Whisky, The Stag and Hounds and the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

By Alan Russell

- 3105 reads

The Stag and Hounds at Braywick between Maidenhead and Windsor is where I had my first taste of English bitter that I paid for legally myself as I was then eighteen years old. It was where I was introduced to and inducted into the tribal rituals of being a customer in a pub. Being one of the regulars, knowing when to buy a round, what subjects were open to conversation and which ones were strictly off limits and knowing precisely the right time to leave for home at the point of reaching contentment before capacity.

The landlord who oversaw my induction was Eric Balderson. A quiet man who always wore a suit, never left the area behind the bar to join the customers except to clear the tables but was always on hand for a chat. Especially if I went in by myself and the place was quiet, I could sit at the bar with my beer and have a conversation with him.

One night I was the only customer left. Eric asked if I could help clear the tables after closing time which I did. Just a few glasses and dirty ashtrays. Then he invited for ‘afters’. I was still only eighteen and the landlord, yes the landlord of the pub had asked me to stay behind for a drink with him. Me, a callow youth who at best could only manage to drink two well spaced out pints in an entire evening. Eric asked me what I would like for ‘afters’.

I politely asked for another beer and a small one at that but Eric wanted me to try something else. He brought down a bottle from the high shelf behind the bar of a whisky called ‘Tormore’. Like a bar man in a Western saloon Eric put two glasses on the bar and poured some Tormore into each of them. The soft amber coloured liquid looked settled and comfortable in the bottom of the glasses.

‘What would you like with it’ Eric asked.

‘American dry and some ice please’ I answered verbalising an effort to appear grown up and sophisticated.

There was a stunned silence filled with shock as if I had farted loudly in a cathedral or the reading room of The British Library.

‘No, no, no, no young man’ Eric remonstrated with me softly but in exasperation.

‘Have a look at the label. What does it say?’ he continued.

I read the label which said the Tormore was one of Scotland’s finest malt whiskeys that had been matured over twelve years in oak barrels on a remote island or in a remote community.

‘Now Alan, why would you want to ruin something that old, that well crafted with ice and even worse, you have some serious learning to do, American Dry? Tonight you will find out what a real proper whisky tastes like’.

I watched Eric hold his glass up to the light and gently swoosh its contents around the inside of the glass like a sommelier would do with a fine wine. I copied him hoping of hopes not to be too enthusiastic with my swooshing and force the contents of the glass across the bar. Eric told me to smell the whisky just like I would a wine. I did and the aroma was on the hot side of warming as it assaulted my nostrils. It was that heat on the first inhalation that hit me hard. I had never smelt anything like it in my life. Dad always had whisky in the house over Christmas. Usually Johnnie Walker or Bells which could smell hot and strong but nothing like the aromas Tormore exuded. I can’t remember enough of that evening to wax lyrical about the bouquet so I couldn’t say today that it smelt of heather, smokey peat fires and fresh sea air.

Then the tasting. Again Eric did this like a sommelier would and got me to copy him. Tip the glass up to the lips, take a draft about the size of a teaspoonful and hold it in your mouth. To my pallet that was only just getting used to the dryness of bitter, the teaspoonful of Tormore for the first few seconds felt like rampantly ignited napalm. Then the burn subsided and the whisky in my mouth took on a warming comforting quality. Then the swallow and the soft warming sensation went through me. No after burn just a soft warming sensation.

While I was savouring my Tormore Eric started to recite some verse which went along the lines of:

Tis a chequerboard of nights and days

And we are but pieces

He recited a few more lines.

I asked where they came from.

‘The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. One of the greatest poets and philosophers that ever lived. Haven’t you heard of him?’.

I had just finished my English A Level and the books were The Woodlanders by Thomas Hardy, The Tempest and Major Barbara. All standard English literature set by an examining board that would have had literary cardiac arrests at the merest suggestion that the A Level English syllabus should include work by a Persian philosopher.

Eric suggested I buy a copy of the book as it would be an excellent introduction into classical poetry.

Our night of sampling Tormore ended as did my introduction to Khayyam when I stepped out of the pub into the cold night air that enveloped my walk home. This is when I reached the conclusion that pubs are like the womb. They are warm, secure, comfortable and free from the tribulations of the outside world. Then at closing time or whenever the customers leave they are born into a world a world of harsh reality.

I did eventually find a copy of The Rubaiyat and read it from cover to cover. I did find the actual verse that Eric enjoyed quoting frequently from behind the bar of the Stag and Hounds. However, despite my best efforts I could not memorise verse like he could to recite t him to prove I had read the work.

In various moves; me from the family home and Eric off to a pub in a valley buried somewhere in The Chiltern Hills eventually lost my copy. Yet I still retained a vague recollection of those lines that Eric was so fond of. ‘It is all a chequerboard of nights and days’, at least that is what I thought he said.

My Dad is decluttering his flat and the other day when I went to see him he gave me a big shopping bag of books.

‘Have a look through there and keep anything you want. The others I’ll give to David (my brother) next time he visits’.

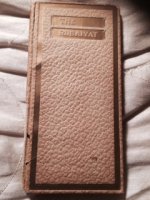

I sorted through what were once my late Mum’s books. There were stories by Margaret Attwood, books about The Guinea Pig Club and Reach For The Sky by Douglas Bader. At the very bottom of the deep bag were two very old books that fascinated me. One was guide from the 1930’s to ‘Bournemouth, Poole and District’ published by Ward Lock. The other book was slim and small and beige in colour. The cover was thin paper made to look like leather. Paper had come off the spine revealing the webbing that held the pages together. The cover was trimmed in gold with a border and the title. And the pages looked like they had been trimmed by a very blunt guillotine as the rolled off the press ready for binding. In raised lettering on the front cover it said ‘The Rubaiyat’. Inside I could see that it was published by the ‘Dodge Publishing Company’ on 220 East 23d Street, New York. On the same page I could see that the original Persian of Omar Khayyam had been translated into English by Edward Fitzgerald, an English poet who lived from 1809 to 1883. He was ‘best known as the first and most famous translator of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam’. So, the English words in this small book were the first translation into English of Persian words from the eleventh and twelfth century. As far as I can establish this particular book was printed in the very early part of the twentieth century and possibly even before World War I.

There are fifty pages containing one hundred and one verses. The first verse starts:

Wake! For the sun who

scatter’d into flight

The stars before him from

the field of night

The last verse (CI in Roman numerals) ends:

Where I made One-turn

Down an empty glass!

TAMAM.

Tamam is Persian for ending and I guess when the glass is empty is as good a time as any to end a poem.

In between are verses that I scanned through looking for the one that Eric so often recited during evenings at the Stag and Hounds. Eventually I found it on page thirty five, verse sixty nine (LXIX). The words were not quite the same as I wanted to remember Eric reciting from that first night of tasting Tormore but they came off the page, not in black and white as patterns to read as words but as if they were being spoken by Eric’s soft tones:

But helpless pieces of the

Game He plays

Upon the chequer-board of

Night and Day.

Hither and thither moves,

and checks, and slays,

And one by one back in the

Closet lays.

- Log in to post comments

Comments

I really like the way you

I really like the way you tied all those disparate things together

- Log in to post comments

Pick of the Day

A lovely little tale - just right for a Sunday evening.

Join us on Facebook and/or Twitter to get a great reading recommendation every day.

- Log in to post comments

Good work, comes full circle

Good work, comes full circle well. Nice, warm, relatable style to the prose

- Log in to post comments

Fascinating insight

I love reading about other lives. Every person has more than enough for a brilliant autobiography.

You probably already know the works of Rumi but, if not, here's a link. I feel you might like him.

- Log in to post comments