Winter Birches

By rosaliekempthorne

- 969 reads

Ash fell like snow. Or the snow like ash. The winter mixed with the burning of her city; there was no real telling them apart. Both of them fell softly, floating on the air, the sting of cold outweighing any residual heat. Sometimes she'd see a flake of ash, still glowing faintly – a floating firefly – and she'd find herself stopping to stare for a moment, stopping to wonder where it had come from, what it'd been once before the sun rose over today and changed everything.

“Neshu!”

She turned.

Her mother was calling back to her. Her voice was shrill and quiet, carried just beneath the wind. She hesitated before wading back through the grass.

Neshu looked downhill. There was hardly anything to see now, the walls of Darkmaiden Pass obscured all but an apricot glow. As if there were just a midwinter fire beyond those bulging rock-faces, nothing worse than apples roasting and fire-dancing... She said – apologetically - “It's snowing.”

“Yes. Neshu, we have to keep going.”

She didn't want to whine, but the words escaped her: “I'm tired.”

“We all are. Look at your sister. She's walking along as doggedly as you please. If she can do this, you can.”

Neshu bit back her resentment, a pointless flare of anger. Her mother was right, there was no time for this. She remembered her father saying the words as they'd been leaving: “we need to keep ahead. By nightfall they'll send out the dogs.”

#

Neshu knew about the dogs. She'd heard stories growing up – worse and more frequent stories as the ships of Ragu Yelsuunn were reported closer each day. Back in the city she'd sat in a circle with other children her age and they'd traded such stories like as if they were precious stones. Yes, the dogs were the size of ponies, they were a white colour, combed through with grey. Like ash, she thought now, putting one foot in front of the other in front of the other in front of other... “Born out of fire,” said a boy from across the road, “cooled on the ashes of bonfires and quickened with the blood of the innocent.” No, she'd thought, no, because her father had taught her that they were only bred, only trained into monsters, that they had noses that were never wrong, latching onto a scent and never letting go. When they found their target they moved in silence, then struck with snake-speed, surging through all and any obstacle, pinning their prey into the ground, closing teeth around their throat...

A skinny girl had whispered: “We all have to die. That was the promise in the letter. So they won't let anybody escape. They won't spare anyone, not even a newborn baby.”

“It's a blood debt,” said another, “it can't be paid except for in full.”

Hunt us down. One by one. Ten by ten. Every soul that had ever sheltered behind Aurellton's walls. Ever.

And so she kept putting one foot in front of the other, in front of the other, in front of the other. It was snowing for certain, and the wind was strong, twisting and weaponising the snowflakes, sending them back at her in a jet of wet-cold, finding their way like nimble fingers through the seams in her dress, through her cloak, up under it, beneath the clasp and then burrowing down her neckline, settling painfully against her chest. Flakes settled in the long grass. Ash or snow. They both settled the same. White. A little grey.

She pulled the cloak around her, even as it did not good. The slopes were steep here, pocked with rough boulders, the grass growing sometimes nearly up to her waist – and it was wet now, brushing wet fingers across her legs, spraying droplets of moisture against her back, along her arms.

One step. Another step. One more step. She kept her head down. She tried to keep up.

The western skyline blushed a shade of darkened purple.

Back in Aurellton, the new masters would be setting loose the dogs.

#

The forest came into view now. It'd always been just over the hill, or the next hill, or the next. But now it was here at last, the canopy iced over white, the interior dark and foreboding, offering the possibility of creeping sprites; gnomes; shiny, black-skinned gremlins.

Her father now carried her sister – too young and tired to go on walking. Two years older, Neshu still felt vindicated. Her feet - aching, burning - still moved of her own volition. She kept going, like the adults did.

She knew there must be more refugees – families, just like her own – but she'd not seen any more than a hint of a human presence since they'd crossed the outer boundary. They'd left the city late though – almost too late – and her father had chosen this way. Most still seeking escape would go by the Capleton road, or would try to slip away along the coast; a few might try their luck in the high hills. The forest: dark, encapsulating, woven through with secrets and old curses: how few would dare that means of escape?

They'd whispered in the dead of night about it: her mother, her father, in a bed a floor above hers. The only way. The best way. Was he certain he could find the path? Yes. It'd not been that many years. Yes, of course.

And now they stepped into the shelter. It was immediately darker, and the air felt different – it was softer and damper, there was a gentle smell of pine, of decay, of vegetation, pollen, perfume. The snow had barely penetrated. Her footsteps were soft against fallen leaves, ferns, grasses, mushrooms. There was a near-silence where the wind could hardly find its way. In the dark up ahead were the twisty woody-white lines of tree trunks.

Neshu's father smiled.

Her mother turned to check on her. “You're all right?”

She nodded.

But her mother fussed over her cloak all the same, trying uselessly to tug it around her, brush off the snow, clear her wet hair from her face. “There. Better? We'll be there soon. Soon.” There: a nebulous possibility. Something neither parent would explain.

And her father: “We should keep moving. The hunt's already on.”

He lead the way. She, and her mother, stumbling after, while Lottia sat on her father's back, cheek against his shoulder blade, not really asleep.

#

They rested in a hollow.

They all listened.

Neshu did because her parents did. And... because you had to... just knowing they must be out there, picking up scents, hunting down stragglers and would-be-escapees. … wash the stones clean with the blood of every soul whose breath and footstep has polluted them.... She'd seen that posted on the city walls. And she listened for the snuffling, for the faint brush of fur against bark, for a fifth breath, a fifth set of lungs – six, seven, eight, nine...? There'd be little sign, they'd be almost silent. The dogs could pass through solid objects – sometimes – their passage along the ground was cushioned by tiny pockets of air – they flew-floated more than they truly ran.

And gremlins too. And ordinary wolves. Poisonous trofoth. The dark fairies who shared hollow-tree homes with the dryads; the oozing, living sap of the legendary Witches' Tree. All these things were real and threatening, shrouded away in a darkness that was nearly within reach. Which could reach at her, extend its dark fingers, find her, easily find her...

Her father explained: “A winter birch, probably a large one, it'll look a bit different, its trunk will be more twisted, bulbous, there may be hints of unexpected colour. There's a dozen or so of them out here.”

It was a big forest. Dwarfing twelve or so trees. Dappled, curvy needles in a nearly dark haystack. But she'd look. Of course. She'd try.

Her mother squeezed water from her cloak, rubbed her whitened hands. “We'll be all right, love. Your father has a plan. He has friends. Now you watch over your sister.”

Baby Lottia. Wayheaded. Simple. She'd clung against their father's back all the way into the forest. Had unexpectedly cried and needed to be shushed. Her vacant, purple eyes clung to everything the forest offered. And now, sleepy, cold, numb, she sat where she'd been put, fat fingers reaching out at blades of grass and tiny red flowers. Picking up stones. Picking up twigs and scrapings of bark.

“Some of the neighbours say there's nowhere to run.”

“Just gossip, my sweet.”

“They all say so.” She considered herself too old now to be fobbed off with platitudes. Death was stalking them. She wasn't sure how afraid she was. She wasn't sure she understood exactly what it all meant. But she knew this: “It's a blood debt. It stays alive until the last of its quarry are killed. It'll just keeping beating at his mind. So he'll have to-”

“Ragu Yelsuunn is a fool, and his curse will haunt him like a heartbeat for the rest of his life.”

“Or his dogs will hunt us all down!”

“Ssh. No. We have friends. We have means others don't have.”

“And Sushesh Weaver, and Lokri Frogsinger? Jodo? Begbin?”

“Hush. We can't do anything about that now. They'll run if they can. Ragu Yelsuunn's dogs only have legs. They haven't wings. We'll stay ahead of them.”

#

The forest wasn't silent, only quiet by comparison to the open spaces. In the night it was made up of sound. This wasn't the howling winds of the hills, the rustle of its grasses. These were deep noises, out here under the trees. There was life in the undergrowth, constant, brazen. The hedgehogs foraging amongst the brambles, squirrels in the branches, night-owls hooting quietly, rats and stoats and weasels flickering in and out of bushes. At times Neshu thought she heard the faint breath of something larger - a soft, wolfish panting. Were the sounds she thought she heard the sound of hunting, tracking paws?

“We're too big a group to fall prey to wolves,” her mother said.

Too big a group for five wolves? For ten? For these packs of fifty or more that some people say still roam the highlands – like the ones that descended on the ruin of Capithallo?

We: another Capithallo?

Aurellton: salted and burned.

And Ragu's famed dogs: she didn't need to ask, she didn't need to hear her mother tell her they would likely never even hear those coming.

Her father. His focus was elsewhere. He tuned her family out. But for good reason. He was hunting one of his trees. And in the thick of it all he held a hand up, his eyes glazed, a soft aura of purpose wrapped itself around him. Then he smiled. “This way. This way.”

#

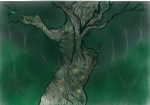

It was a fine tree, impressive, outcast – set away from others in the forest; its roots had erupted again from the forest floor, building a cage, a nest, around it. It's profile was snakelike, a huge wooden serpent coiling itself around the air, bark that was smooth, white and pale brown, twirling and flowing, while small colonies of moss, lichen, mushrooms grew along its trunk. The moss was tinged blue, and the bark tinged barely pink.

Neshu's father walked over to the tree. He ran his palm over the bark, and the scratches appeared. As easily, as simply as that. They looked as if they could have been carved there by children, but she knew they hadn't been. There was a faint glow that formed in them, markings that didn't seem to make immediate sense. Or... then... It was a map, wasn't it? And her father seemed to know where it went.

“Are we saved?”

“Hush. Yes. But I think they're coming.”

“The-”

“Yes. Hurry.”

Because they wouldn't hear them coming. Or smell or see or sense? And yet her father had. He still could. She was sure of that. She could hardly keep the pace he set, dragging them through thickets and copses of painful nettles. She was too big, and her mother was tootired, and her travel-sore father had Lottia already, so she couldn't be carried, she had to run, she simply had to keep up. Though her lungs screamed and burned, though she stumbled.

There were sounds in the bushes. So faint. And a sense in the air of cold, a sense of thickening and awakening, a buzzing in her ears, a physical sensation as if tiny gnats crawled all over her ears, formed a line, set their plans for a deeper invasion.

The can smell us, can't they? For over a hundred miles...

The second tree was straight and dark. The symbols on it had been carved and painted. There was a narrow, misty line that ran down its centre. Neshu's father said, “Follow me.” And he turned sideways, sliding his hand, then his arm, then his shoulder into the line of mist. Neshu's eyes widened, watching him disappear. She saw Lottia stiffen in belated panic as the mist swallowed her too.

“But where does it go?”

“Does it matter?” Her mother gripped her wrist and pulled her in.

Too thin, too narrow to fit a human, to fit a grown man, or an eight-year-old girl, and yet she slid inside, finding herself in a hallway too narrow to stand facing forwards. Even she had to stand sideways. He father, up ahead, stood with Lottia by his side – too big a lump to keep on his back now – and her mother stood next to her, back against a wall made of ebony, encrusted with symbols, studded with strange small items: scissors, dice, spoons, jewellery. From somewhere further ahead, a dim, white light shone. And there was the faint sound of what seemed like human voices. A trace of warmth coming too from that direction.

Neshu looked up at her mother: “Are we safe then?”

She lay a hand on her shoulder. “For now,” she said, sighing, tilting her head back. “For now at least, we are.”

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Stunning IP. Such a complete

Stunning IP. Such a complete, living, breathing world. Please write the novel.

- Log in to post comments

Pick of the Day

A great tale - full of mystery and suspense. You build a whole new world quickly and economically. Fine writing. Easy to pick this for the day!

- Log in to post comments

I genuinely want to know what

I genuinely want to know what happens to the family, to know more about how this world works. Is there to be a sequel?

There were a couple of typos here and there and bits of awkward phrasing (nothing an editor's touch can't fix), but I think you've got a great handle on world-building here; you've created what feels like a rich and complex world, while keeping the narrative itself simple and straightforward. Well done.

- Log in to post comments