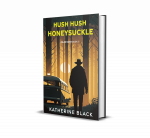

Silas Nash Book 1 Hush Hush Honeysuckle: Chapter 4

By Sooz006

- 486 reads

The next day coffee shop-girl—Paige—was still on his mind. Thinking about a pretty girl was easier than thinking about a dead nanny.

Despite that, he went back to the first memory he could drum up and tried to go back further. There wasn’t a single day in his life when Nanny Clare wasn’t there for him and his sister Melissa. They were wealthy, and people who haven't got money have a misconception that being rich automatically means being happy. It doesn’t matter how many songs tell you that money don’t buy you love, other people—the ones without a platinum card—expect you to be delirious. If you aren’t a Happy Joe, it’s as though you’re letting the side down.

Mel was all right. She was one of those people that didn’t mind being on her own. Max didn’t know how Laurence put up with her. When he bothered to think about it deeper, he realised it was because Laurence was a doormat. He knew his place and kept it.

Max wasn’t like his sister. He wanted his parent’s love. He’d go so far as to say he had an unhappy childhood. Poor little rich boy and all that. His parents had children and then realised that life was more fun without them. They sailed around the world doing their thing, and somehow—though Max never understood how— spending money made money, and they grew richer every second.

They had enough money for themselves, the staff, and their various affairs. Though that was mostly to pay the gigolos and mistresses off when it turned ugly. They didn’t skimp on their children, and there was always a trust fund for every time they felt lonely.

When Max was nine, and it came to the divorce, the money wasn’t enough for either parent they each wanted more than they could ever spend. They’d lived in a huge townhouse, long since sold now, but Max could hear them screaming at each other wherever he was. And Nanny Clare would come to him in the playroom and pass him his PlayStation controller. Grand Theft Auto III made everything better.

And she’d sing Rhianna songs to him until the shouting was over. She was a Geordie born and bred, and he was her sensitive bairn.

There was always Nanny Clare. And now there wasn’t. How did that work?

He was shocked to walk into the tiny wooden church and see that he was the only mourner. There was Max, a priest and one bored-looking altar boy who was swinging incense about as if he was passing a ganja pipe around.

Max laughed at the irony of the pomp. As well as paying for this farce of a funeral, he’d booked an events room and paid for a buffet for fifty. Clare would love that. He wondered how long the staff at the wake would leave the sandwiches to curl before they realised that nobody was coming. He’d put out a sombre message for the occasion on social media, welcoming everybody, and he’d put the standard obituary in the newspaper—figuring she was of that age. But nobody was there. Not one person. Shame on them all.

As an adult, Max had never stopped visiting her. She was involved in every major decision of his life. She’d even advised on some of his business ventures. Max owned her cottage, but she lived there alone. He couldn’t give it to her—she was too proud. But he’d spent ages finding just the right place for Nanny. He said he needed a caretaker to look after it for him, so she’d spent the last ten years there rent-free under the guise of being a hostess, even though she’d never had a single visitor other than Max. She didn’t like the word caretaker, and she said she was happy.

He took his phone out while he was on his knees in that moment of quiet reflection. He texted Mel. Where the hell are you?

I can’t make it. Sebastian’s sick.

Your seventeen-year-old, Sebastian. That Sebastian? ‘Piss off, Melissa,’ he hissed.

The priest coughed and crossed himself, and the altar boy opened his eyes properly for the first time.

‘Sorry, Father.’

Every few months, they went out for one of those fancy cream teas that cost a fortune, particularly on the day given over to thanking your mother for having you. He told her, ‘You brought me up. You’re the only one that deserves the fuss on Mother’s Day.’ He’d pour her some tea out of a teapot with honeysuckle painted on the side. He loved watching her choose her tiny sandwich and cake. These outings reminded him of Mel’s tea parties with all of her stuffed toys and dolls lined up and the tiny plastic tea set that she loved. Then one day, in a fit of spite, he’d filled the teapot with Das modelling clay, and it set like concrete, and that was that. Poor Mr Sniffles, the stuffed dog nightdress case, had to do without his cup of tea.

Nanny Clare would only have one of each, a little sandwich—usually salmon—cut into a rectangle with no crusts, and that charmed her. ‘I do hope they give the crusts to the birds. They won’t waste them, will they, Barty?’ she’d say, using the pet name that infuriated him as a child. Her fingers would float over every cake, and her rheumy eyes would sparkle like pale emeralds as she made her choice.

She always went for the miniature strawberry tart, which she ate with a knife and fork. She tried to be very posh, and Max would suppress a laugh as the Geordie in her tripped her up at the first piece of cutlery.

Max would eat more, but it wasn’t his kind of food. He’d rather have a juicy steak, so most of the tiny food items would sit on the three-tiered cake stand to be returned to the kitchen. He had to tell her that the waitresses would enjoy them during their break to stop her worrying.

‘Barty, you’re spoiling me. You naughty boy,’ she’d say. And as he sat on the hard wooden pew, he felt the tears as he remembered her. He didn’t mind when she called him Barty anymore, even when they were eating out, and a business associate came to say hello. He loved being told off by her, even at twenty-eight. It was the only time she ever called him Maxwell. ‘Maxwell Jones, I’m warning you, if you don’t get your hair cut, you’ll never meet a nice girl. And stop calling it Barra. You live in Barrow, dear. Didn’t that fancy boarding school teach you nothing? You’d better be kind to your sister. She won’t always be around, you know.’ And here they were. Mel was going to live a long and miserable life, and he would be gone. Until today when she was laid in satin, not one swear word had ever left his lips in Nanny Clare’s presence. He respected her too much for that and was going to miss her—bloody hell.

They wanted him to go up to the coffin. He just saw a fancy box. For all he knew, Nanny Clare might not even be in there. They might have sold her to make ancient Eastern medicine. She was ancient. Nanny Clare would mix well with a couple of snakeheads and a bit of rhinoceros horn.

‘See you very soon, Nanny. Coming ready or not,’ he whispered, kissing his fingertips and dropping them onto the lid of the coffin. He felt that’s what was expected.

The funeral curtain came across, and the priest said another load of meaningless prayers, presumably to give the gravediggers-cum-pallbearers the chance to carry old Nanny to her grave. He smiled when he heard one of them grunt as they took the weight of the casket off the gurney. Nanny would have tutted.

Father Murphy Sang Lord of the Dance and Max mumbled the odd word out of tune. The altar boy seemed to manage the last word of every second line until the chorus, and then he still didn’t sing, but he jigged side-to-side a bit to show willing. It was a rousing number. If he’d had more time, he’d like to have made the funeral grander for her, maybe hired a hundred mourners from an agency. And he’d like to have made the altar boy smile. He remembered what it was like when your parents forced you to be one. They had no idea the ribbing Max took for wearing that white dress. His best friend, Bobby, wasn’t Catholic, and the other one, Jon, had a mother that listened to him when he said he’d rather die than go to church. Which was probably an exaggeration, but Max was still in awe when she didn’t force him.

They left the chapel and made a sad parade, the three of them walking down the path to the cemetery. The altar boy had swapped his thurible for a huge black umbrella that he held over the priest’s head in the drizzling rain. ‘The kind that gets you wet,’ Nanny would have said. Father Murphy was dry, but pathetic little Tommy Tucker, or whatever he was called, was sodden.

Father Murphy strayed off the cinder path to the grass verge and stepped in some dog dirt. Max and the altar boy could tell how much he wanted to swear as he wiped the side of his shoe. He didn’t swear, but he did mutter under his breath. Max nudged the boy from behind, and they both snorted. The boy, more used to the priest’s lack of humour, hid his laughter better.

‘Yes, quite,’ Father Murphy said, and neither one of them could hold it in any longer.

‘Please. Respect.’

‘Sorry, Father,’ Max said and blessed himself for good measure.

At the graveside, the priest stood at the head of the grave.

The old man was cold, and Max saw him shiver. The boy held the big umbrella over his head, but the wind kept taking it, and the lad was only short. It clunked the priest on his head. He didn’t look pleased in the grace of God, and Max didn’t think the prayers were supposed to be said as fast as they were.

He lowered his head and clasped his hands together. For the first time ever at a funeral, he didn’t think about how fast he could get to the pub—not the one with the buffet, any other—for his first pint. He remembered Nanny Clare—his Clare and all the good times and bad times. And all the ones when she’d changed the course of his life for the better.

‘We, therefore, commit this body to the ground. Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.’

Max felt the priest’s hand on his shoulder, and he cried quietly. When he raised his head, they were gone, and he was alone at the open graveside.

‘It’s just you and me, Nanny. I’m not happy with you for leaving me, you know. But guess what? I get the strawberry tart from now on.’ He sat down in his eight hundred-pound suit and let the rain wash over his face. It wasn’t raining when he came out, so he didn’t wear his ash-grey overcoat, bought especially for funerals. He went to a lot of funerals for his aged business contacts.

He dangled his legs over the hole of Nanny’s grave. She wouldn’t mind, or maybe she would. She was always one for proprietary, but what could she do about it now? He smiled at the memory of her face of disapproval. He glanced at the sky to see if she was pointing down at him through the clouds and then grinned because he’d imagined her telling him off again. Just like always.

‘I’ve met a girl, Nanny. She’s really pretty. I might bring her to meet you one day.’

He stood up and dusted down his wet trousers. They were ruined—just like his life.

‘I’m going to get her, Nanny.’

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Laurence was a doormat.

Laurence was a doormat. (cliché patrol). He knew his place and kept it. This is an example of overwriting. If you use the term ‘doormat’, I’d suggest you don’t need to explain it. Readers get what a doormat is both as a thing and a person.

She was a Geordie born and bred, ![]() and he was her sensitive bairn.

and he was her sensitive bairn.

Then one day, in a fit of spite,![]()

and it set like concrete,

suppress a laugh as the Geordie in her tripped her up at the first piece of cutlery. [too many hers here and not enough clairty]

He’d rather have a juicy steak. Juicy steak is a cliché. You could write: He’d rather have a steak. That’s what I’d write. But if you are trying to portray a way of write as they speak (I can’t remember the technical name for it) then juicy is better.

going to live a long and miserable life, and he would be gone.

neither one of them could hold it in any longer. [neither of them]

The boy held the big umbrella over his head, but the wind kept taking it, and the lad was only short. It clunked the priest on his head. [short boy/big umbrella. I know what you’re doing, but it’s muddled] semantics.

Altar boy>umbrella>wind>priest’s head.

For the first time ever

changed the course of his life for the better.

he cried quietly. When he raised his head, they were gone, and he was alone at the open graveside. [you say the same thing twice. cf he cried alone at the graveside.

rain wash over his face

business contacts. This might need a possessive. Businees' contacts.

dangled his legs over the hole

stood up and dusted down

Jacob Rees-Moggs took his nanny when he was electioneernig for the first time. I think it was Dundee. We don't like Tory scum up here, with or without his nanny.

- Log in to post comments

It was nice to read a more

It was nice to read a more sensitive side to Max.

Jenny.

- Log in to post comments